What Went Wrong

The path of literacy's decline was paved with good intentions

I greatly enjoyed

’s recent essay “The Cost of Standardization.”Likewise, I have been fond of ’s recent pieces “Why Mastery Doesn’t Matter” and “AI Schools Are Selling a Dangerous Fantasy.” I also often find myself nodding along in agreement with , whose arguments might most neatly be summarized by his publication’s title: “Play Makes Us Human.”1 Collectively, these writers are saying something that I largely agree with: K-12 public education in the 21st century hasn’t been working—has become counter-productive, in fact. The vaunted recently took notice, if tangentially, in his letter “A Crisis…” in which he discussed our transition from “a literate to a post-literate culture.” At the end of his missive, he asked,“For those of you who are educators – what are you seeing? What has changed in, say, the last fifteen years? What, if anything, can be done to reverse things? Are there existing programs and approaches that are working?”

I have my own recent answer to this question in my essay “Notes on a Toxic Pedagogy.” In general, I and many other educators have been arguing for some time that our movement to a standardized and mastery-based education has had terribly negative consequences. In my own classroom, I have been arguing that our intelligence was becoming artificial years before Chat GPT came onto the scene. We in the schools had already drastically reduced much of our curricula, were already catering to our perceptions of students’ shortened attention spans by assigning shorter readings, had already removed a great deal of challenging material from our curricula, had already cut art and music electives, and, as a culture, had long ago divided into separate camps receiving separate news from separate sources, repeating talking points from talking heads as if they were our own opinions in pantomimes of actual thought.

Still, the machine rolls on. In a comment responding to my “Pedagogy” piece, a former AP English teacher turned administrator, since retired, wrote:

I do think there were and are legitimate concerns about ensuring that all students had a fair opportunity to learn, especially in the context of historical/institutional racism and gross economic disparities. In addition, access for students with learning disabilities became a newish and very important concern.

I don’t think it was very convincing for teachers to say, “trust me....(everything else you write here.)” I do think we often failed to describe outcomes for students that were visible/measurable to concerned constituencies, especially those representing the students I note above. I still think that’s a major issue for public education. We also need to say what we are trying to do about it. That’s where pedagogy comes in. There are vast seas of BS out there, but I think good teachers need to be able to show others what the goals are, (best through examples of the craft that students will produce,) how you can tell students and others that they are making progress toward them and what you are doing to help students who aren’t making the progress they could.

A ceramicist can show examples of what her craft will produce. So can a chef, a cabinet maker, etc.

I have found that even some teachers who are perceived to be great have a hard drive with this. I do think this is critical and is an essential response to the absurd lists of “measurable student learning outcomes” and pretest-post test ridiculousness that distract vast amounts of time from much more valuable learning in all disciplines.

The boldings are my own. I share this long quote in an attempt to demonstrate how complex the issues are. The commenter doesn’t entirely disagree with me, but points out ways by which, in education, our hands are often tied. In 2011, I asked an administrator at my school—an ethnically diverse, low-SES, ‘failing,’ public high school that had ‘turned around’ its test scores by drastically narrowing its curriculum—what we had really gained through No Child Left Behind, and if our students were better off now than they had been before. His own response anticipates the comment I’ve shared above: There were an awful lot of students who were being under-served in the old curriculum, and an awful lot of teachers whose practices were inefficient. The testing helped us identify these problems and shortcoming so that we could address them.

This is a hard argument to refute in the twenty-first century. Equity is considered in many quarters a supreme, unquestionable good, tied up closely with justice. To question the ‘good’ of equity is to immediately leave oneself open to charges of discrimination—discrimination in terms of race, gender, and abledness—and be swiftly decried as morally repugnant. To do something in pursuit of equity is to put oneself beyond the reach of criticism. But I think that people with good intentions can do terrible harm. In my old school, we achieved the illusion of equity by raising our test scores, but enormous numbers of our students were underserved and mal-educated in the process. Many of these students wanted to go to college. They could have and should have received educations more closely comparable to better-off students in better-off parts of the state. Large numbers of these underserved students were members of historically marginalized groups—first-, second-, and third-generation immigrants, English as a Second Language students, young women, differently abled students, low-income students, etc. Students who could have and would have benefitted from a broader, deeper curriculum but were denied that curriculum so that we could raise all students to pass the tests.2

We have a name for the way those students’ educations were curtailed and limited in that minority-majority school: institutional racism. I don’t hesitate to use it.

The teachers I worked with in that building, passionate educational craftspeople adept at searching out and feeling what was best for all students, cried out for our disenfranchised students—not merely our highest achievers, but the students in the middle and at the bottom, too, who were treated to lesser educations than they deserved. The response we were faced with was telling: if we didn’t raise the test scores, the state could ‘clean house.’ They could fire administrators and teachers and institute state control over the school.3

They could fire administrators and teachers and institute state control over the school. This is not an argument for doing what’s best for the kids. This is an institutional argument for doing what is best for the administrators and staff. Indeed, during NCLB, how many kids stopped hearing that their educations were for their own benefit and started hearing ‘you have to pass the test so that your teacher can keep her job,’ or ‘you must pass so that the school can stay open’? At the height of NCLB, parents were parking their cars in the street around their schools in low-SES districts and praying in hopes of their children passing the tests so the schools that served them could stay open.

Which is all to say, standardization is a terrible ‘good’ to aspire to. By its nature, standardization is reductive. In practice, it stops teachers from playing to their strengths, stops them from responding in unique ways to the unique compositions of their classrooms, and prevents teachers from cultivating environments that are genuine and authentic in which students, many of whom get too little interaction with responsible, caring adults to begin with, get to interact authentically with adults who have their best interests at heart. In education, standardization too often narrows students’ horizons at a time in life when those horizons should be stretched out. Too often, it means that teachers reduce the challenges we offer students to the ‘safe’ space of what we know they can accomplish instead of sailing with them to the more challenging waters in which some of them might not be successful. If the NCLB movement did us the favor of helping identify which students were being underserved, that favor has been done, and the subsequent repercussions of the standardized testing and ‘mastery’ movements have largely been negative.

I hold it as an axiomatic truth that the more something matters, the harder it is to measure.4 Student argumentative writing assessments, for example, are more difficult to measure than multiple-choice tests—one must take the time to read the essays; one must create effective rubrics; one must learn to use the rubrics; one must be an effective critical thinker, oneself—but the argumentative essays are certainly deeper proofs of students’ abilities to critically think than the M/C tests. What’s more, assigned argumentative essays, whether ultimately successful or not, students actually do the cognitive labor of trying to write the essays: they are challenged and given the opportunity to grow. Many states don’t assign argumentative essay assessments anymore, though (mine doesn’t), and we all assign M/C tests. And in the modern age, if we don’t test it, we don’t teach it, so many of these activities that actively develop critical thinking abilities—reading long texts; reading ‘difficult’ texts; writing longer analytical and evaluative papers; conducting research—have been relegated out of the curriculum in favor of preparation for multiple-choice tests that are, by their nature, shallow proofs of educational proficiency that are easy to prep for and easy to pass.

“A ceramicist can show examples of what her craft will produce. So can a chef, a cabinet maker, etc,” wrote my commenter, and in the last two weeks I have visited the classroom in my high school where one of our teachers teaches ceramics. I also visited the FACS room where a teacher leads students who will one day become chefs—or simply cook affordable and nutritious meals at home. In the first, the walls were lined with all manner of pieces of pottery, many of varying degrees of quality, many very good. In the second room I was treated to a ‘breakfast cookie’ that the students had made. It featured coconut, oatmeal, and chocolate chips, and was delicious. Both of these teachers were excellent instructors. Both of them taught wildly popular classes. I would love my own children to be in either of these rooms for an hour and a half every other day. But back upstairs in my own classroom, I couldn’t help but think I am not a ceramicist or a chef. I’m an English teacher. The fruits of my labor are abstract and difficult to see. I produce critical thinkers who can analyze, evaluate, and synthesize. I give my students frameworks of understanding which they can apply to the world. I introduce them to common cultural touchstones. I help them identify bias. I help them grow in their abilities to speak—and agree or disagree—in conversation with one another. I plant seeds that may sprout and yield fruit in coming years—or not. In my essay Notes on a Toxic Pedagogy, I mentioned Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein and the manifold ways I wanted students to learn and benefit from it. The benefits of reading a novel like Shelley’s are, I think, immeasurable. The book, as illustrated again by a new movie in the last few weeks, famously defies filmmakers’ attempts to convert Shelley’s art to film. Because it is difficult to measure what my students learn from this text, does that mean I shouldn’t teach it? To many contemporary educational administrators, ‘thinkers,’ commentators, and ideologues, the answer is Yes. To them, I say You have impoverished us.

Short-term findings/ Long-term consequences

I’m dubious of ‘the data.’ I’m bothered when district’s write in their mission statements that they are interested in using ‘the newest’ researched educational techniques when it seems clear to me that they should be searching out ‘the most proven.’ Our mania for ‘the new’ is largely at fault, here, but more so than that, we have impoverished ourselves by chasing easy educations that we know we can measure at the expense of more difficult educations that are more difficult to gauge. Further, it seems to me that many studies on education are limited by their short-term durations. If you have a student do short, closely guided, intense bouts of study, of course you are going to get good results from that strategy in the short term—but what happens when you hammer students with short, closely guided, intense bouts of study every day, day after day, year after year? Do you burn them out? Do they develop coping strategies, like shortcuts or ways of cheating, to avoid the monotony and intensity of it? I believe they do. Further, if you only train students with Explicit, Direct Instruction (EDI), the way an animal trainer might prepare a dog or bird to perform in a circus, of course you will get good results on your measurable tests, but will you have produced students who can actually think and solve unpredictable and unanticipated problems in the real world? I’m a little dubious.

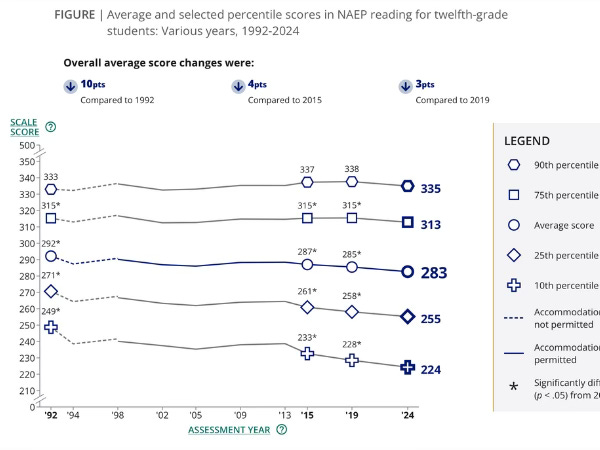

NAEP reading scores for 12th grade students, 1992-2024

In the long term during this ‘age of measurability,’ all scores are stagnant, and the students in the bottom quartile and decile, who were supposed to be getting the most attention, have suffered the worst declines. Note the mirage of ‘lift’ during NCLB as schools faced increased pressures to pass the test ‘or else,’ and the fact the plummeting began years before the pandemic. We did an awful lot of research, hired an awful lot of administrators, retrained and chased out an awful lot of teachers, and imposed an awful lot of misery to achieve these losses.

The long-term findings are, I think, damning. Many will blame our movement to a ‘post-literate’ culture on smart phones and social media, but I see the seeds of something we planted in 2002—NCLB and the standardized testing and ‘mastery’ movements—coming to fruition. If you want to produce readers and a literate society, you don’t do it by training kids to pass tests, you do it by teaching them to love reading, and training kids to pass tests has the unsurprising consequence of making them hate reading. If you want to shorten the loops of instruction and make use of intensive EDI to train kids to pass standardized tests, you might get those kids to pass those tests, but you’ll also teach them that it’s their scores that matter, not their educations, and the constant sense of their being measured will have negative consequences in the long run on their internal vs external motivational systems and their mental health—you’ll incite an awful lot of anxiety.

“I don’t think it was very convincing for teachers to say, “trust me....”, my commenter wrote, but I think the onus is on the administrators, bureaucrats, and ideologues now. They traded rich curricula and trust in classroom teachers for short-term numerical gains and data’s ephemeral mirages of progress. The long-term and, I think, more trustworthy data tells a troubling story about the last twenty years: educational stagnation, mental health crises among young people, a literacy crisis, high rates of absenteeism, teachers leaving the profession in droves, and fewer young people wanting to become teachers after experiencing education the way we have begun to inflict it…

I don’t expect us to turn around this doomed ship of education anytime soon. We’ve invested far too much in standardization and mastery; we’ve gone too far in rewriting our curricula and narrowing the training of our up-and-coming new teachers. We’ve hired too many administrators at the federal, state, and local levels to enact our three-ring circuses of data production. Far too much legislative discussion has gone into it; the easy numbers purporting to represent ‘reading ability’ and ‘math ability’ make it too easy for reporters to report. The short-term data, so easy to manipulate, is too tasty a treat for our society to give up—we’ve acquired a junk-food taste for shallow, nutritionally empty information to base our debates upon; the publish-or-perish model in academia and enormous number of academics who need data to further their own careers requires k-12 classrooms to become laboratories churning numbers out. There’s an enormous class of ‘consultants’ who charge low-achieving districts astronomical fees so they can visit classrooms and share acronyms, platitudes, and fad instructional practices to improve standardized scores. I don’t think we’ll give up all of those satisfying moving parts and columns of numbers for a solution so simple as “have kids read more and have them write more; have them speak more and let them play more; test the kids less and trust the teachers and their processes more”—but I think we should.

Peter Shull is a novelist, short story writer, and educator. His novel Why Teach?, a story of youth, education, and bureaucratic absurdity, has been called “A quintessential novel of the No Child Left Behind era” and “A supreme twenty-first century coming-of-age tale.” The first chapter is available to preview here on Substack, and the book is available for purchase at Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo.

Peter Gray’s article “Socially Prescribed Perfectionism is Harming our Kids” is representative of the writing he is doing that I largely agree with.

Damningly, of course, the state tests that are not tied to students’ grades or their entrance into future educational or professional opportunities are not good indicators of ability; many students—sixteen and seventeen years old, deep in a famously aloof, indifferent, and rebellious stage of adolescence—underperformed simply because they didn’t care to suffer through hours of tests that didn’t seem relevant to them.

Had the state indeed ‘cleaned house,’ I’d have been interested in seeing how it went about taking over our school district (and high school of 2,000 students) in a ‘big’ little meatpacking town in Western Kansas. The district already had a terrible time attracting teachers and administrators; the staff we had, if scoring poorly on state standardized tests, did a remarkably admirable job, I think, of working with a population of largely disadvantaged students. (Sometimes a kid doesn’t come out of high school with great reading or math scores, but they leave with other tangible and intangible gains: they learned to speak and read English, perhaps, or developed improved personal habits. They might have managed to get through four years without dropping out, as many with little hope do, or without developing a drug or alcohol habit. They might have picked up auto-shop or computer or nursing skills that helped them end up employable and get a job… There are many immeasurable benefits a high school education can offer. Focusing inordinately on reading and math erodes teachers’ abilities to deliver these other, sometimes difficult to quantify benefits to students.) Likely the administrators at the top—superintendents and school principals, the ones applying all of the downward pressure—were the most likely to lose their jobs, and those who the state brought in to replace them would have been flummoxed, too, by the myriad difficulties of educating a large, diverse, largely ESL, largely low-SES, largely migrant student population.

Can you quantify how much you love your mother, spouse, or child? How much your dreams mean to you? How good a painting in the Musee d’Orsay is? How much it means to spend a holiday with family, or simply make a new friend?

Really thought-provoking essay! You put something into clear words that I have observed in a different discipline/context: I have been a community college biology instructor for well over 2 decades. Over this time I have noticed that incoming students are less and less able to ‘explore’ for loss of a better word. They have a hard time with anything that may have more than one answer and are reluctant to even start exploring something that may have more than one answer. I spend a lot of time coaxing. I have had to slow down a lot more, and also break concepts down more and practice more in order to build confidence in anything that isn’t more than a tiny snippet that could be asked in a MC question. The students have been so thoroughly trained to meet a standard and a ‘right’ answer, that they have to learn nuance, multiple solutions, or joining several smaller concepts into something more complex. They are good a maybe picking out the best answer from a few choices, but they can’t explain their own reasoning in their own words. This semester I have an older student that went to K-12 before this standardization craze, and I see the difference so clearly.

At any rate, I also run a grant scholarship program to support underrepresented minority students to persist in STEM majors because the US is not training enough STEM professionals for the current and future needs of the country. But, from my experience, the country is also losing so much by the way that K-12 has trained students on terms of innovation and exploration as well as in-depth expertise. A STEM professional working only to standards isn’t going to drive innovation or solve long-standing problems. But the real tragedy is in the loss of human potential and the joy that comes from developing that potential. Many students do finally have a chance to develop this in college but the standardized curriculum has also been creeping into especially lower division education. Equity is always on my mind, but what is happening in K-12 does not seem to be the right way to go about it.

Peter — really grateful for the love and the thinking in this essay. I appreciate how seriously you take the long view of the accountability era, and I recognize so much of what you describe from my own experience. The narrowing of curriculum, the test-prep rituals, the pressure that shifted the focus away from kids and toward institutional survival — those were real distortions, and in many cases they hit the exact students who deserved the richest experiences.

Your prescription — “have kids read more and have them write more; have them speak more and let them play more; test the kids less and trust the teachers and their processes more” — is, in my book, dead on.

As I sit with that, I find myself wondering whether the real problem is less the existence of tests and more the way we’ve chosen to respond to the data they generate. In my experience, kids who are actually doing rigorous, consistent reading and writing and talking — work anchored in whole books and real intellectual engagement — tend to perform quite well on these exams. Growth metrics on high-stakes tests often do tell us something about how much thinking actually happened in a classroom over the course of a year. I still think we over-test (wildly so,) but I also see value in that signal.

The harm seems to come when we interpret test scores through a “mastery checklist” lens and then reduce instruction to isolated skills in response. That’s the part that feels toxic to me — the idea that comprehension can be reverse-engineered one standard at a time, and that an entire adaptive-learning, mastery-based profit complex has risen up in its wake, replacing time for, well, actual reading and writing.

We often talk about this as if it’s a trade-off — “well, we’re getting better results, but it’s harmful in the long haul…” But I think the most potent argument is the one you make here: it’s not a trade-off at all. Skill-drill programs suppress long-term learning and short-term results. Good instruction — the kind of reading, writing, speaking, and authentic engagement you’re defending — drives rich life outcomes and, almost incidentally, strong metrics. Kids learn, and it shows.

Would love to hear your thoughts. I always value your writing and thinking. 🙌🏻