Teaching isn't a Science - or an Art

Or a business, for that matter.

We’re midway through April. All over the country, teachers are turning in their resignations—they won’t be back in the fall. This isn’t anything new in the last twenty years, but it is a problem that’s getting progressively worse. As with the last several years, there will be fewer fully-trained, fully-qualified teachers available to replace them. If you live in a better-off area—a suburb, or the nicer part of a big city—this won’t affect you too badly, or too immediately, but the teacher turnover epidemic and dearth of young people pursuing the profession is starting to take a toll on better-off areas, too. For areas that aren’t so lucky—rural places; the less affluent parts of big cities—the impact of teacher shortages has been impacting students for decades. There are a number of reasons for this, and we’ve already suffered a number of consequences, but today I just want to focus on one narrow aspect I believe contributes to the problem: that is, the way we view the teaching profession. The way teaching has been framed in public discourse matters. Is it a science? An art? A business? Something else entirely? I’ll share my thoughts below, and I welcome your agreement, disagreement, or other thoughts in the comments below!

Illustration from the second chapter of Why Teach? Art credit: Maurice Olin

Science:

The longer I teach, the less I’m sure the word “pedagogy”—the science of teaching— should be applied to what I do. Don’t get me wrong—my pedagogy is strong. I know all about Bloom’s taxonomy, zones of proximal development, and child psychology. I’m familiar with ‘high yield’ instructional techniques and know how and when to use Direct Instruction, how to guide Student Inquiry, and how to facilitate Project-Based Learning. I can teach to the test with the very best of them. I apply these understandings in my classroom all day, every day. But the notion that teaching is a science has come to seem increasingly problematic in my eyes—I’ve begun to see it as enormously damaging, in fact.

Leaving aside the facts that the word science ought to be inscribed on a pretty big umbrella and that it can be a pretty messy discipline, what people seem to want when they say ‘teaching is a science’ is something neat and tidy: a science of knowing, without gray areas, where environments are controlled, variables limited, and certain inputs will always yield certain outputs. They're after that science that is so often prefaced by the word exact: the science of systemization and sterility: the ‘clean room’ laboratory; the churned-out, reproducible results. But that’s not how teaching works. Teaching is inexact. It’s messy.

With regard to variables and controlled environments? Forget about it. Teachers have to deal with snow days, fire drills, and unexpected intercom announcements. Sudden expectations that we incorporate a newly legislated unit on Constitution Day. New technology. Pandemics. Kids who are late, skipped breakfast, stayed up too late working on homework for other classes. Students more interested in the week’s game, the school musical, the phone in their pocket… Kids who’s parents are divorced, divorcing, or have substance abuse problems. Have been incarcerated. Have been deported. 28 students with varying degrees of preparedness, varying interests, varying home lives, varying motivations. The kids mostly show up, are mostly on time, and mostly stay in their seats during most of the block (though we are working with the most hydrated generation ever, with students who ask to go to the bathroom far more often than previous generations), but a cursory glance at any American classroom ought to demonstrate that a ‘controlled environment’ with ‘controlled variables’ is a far cry from what today’s teachers are working with.

And there are consequences for this sterile, highly structured, ‘scientific’ view of teaching. In pursuit of fewer variables and results we can reproduce, we narrow the curriculum. We shorten the horizon we’re looking out on. At a time when the world ought to be seeming bigger and bigger to kids, we try to make it smaller. Believing that teachers with degrees in pedagogy ought to always be able to wrangle the manifold variables in their classrooms into line and get uniform results, we call them failures when they don’t. The belief that teaching is a science, I think, is one of the chief causes of the stories one often hears about new teachers going home and crying at the end of the day, every day. Why didn’t my teaching work? Why didn’t my students learn? This is a large part of the reason that so many new teachers give up within their first three years in the profession: it turns out mere planning, subject knowledge, and pedagogical knowledge aren’t enough. I’ve seen several highly-organized, highly-intelligent, highly-knowledgeable teachers who have come to the profession with their binders of lesson plans ready—new teachers who work like demons every evening and all weekend long and were likely more proficient in their studies of pedagogy than many other educators—and the winds and buffets of education have had a way of battering and breaking these scientifically-proficient teachers down. The many variables of the job are harder for them to weather than teachers who are less scientific—less reliant on ‘knowing’—and more often than not, these would-be outstanding educators wash out: they leave feeling like failures and pursue different, more predictable lines of work.

Art:

If education isn’t a science, it must be an art. That’s the binary we’ve developed, isn’t it? Left-brain verses right? Organized and scientific verses hippy-dippy and creative?

This is, admittedly, the way I long thought about teaching.

But when you take a cursory look at art, artists, and what artists do, you realize that the making of art and the teaching of classes don’t exactly dovetail, either. And art, when you really look at it, seems more similar to science than teaching. The artist, like the scientist, controls variables. They adhere to habits and rituals. They most often work in controlled environments. Great art comes from working within confines, boundaries, and rules—limitations enable art—and artists set parameters by subscribing to genres, setting boundaries with the edges of their canvases, choosing mediums, and making rules for themselves. Necessity, the imposing of these limitations, is the mother of artists’ inventions. Artists may be seeking—and through their art may encourage others to seek—but most often the practice of making their art is private, solitary, and tightly controlled. If artists collaborate, they do so with carefully chosen peers or apprentices—other artists who have subscribed willingly—determinedly—to the task. Teachers work in rooms that are only organized and controlled if they can bring and maintain that organization. They deal, as mentioned above, with unexpected variables aplenty—and sometimes these unexpected variables are the “happy little accidents” that a Bob Ross might have incorporated into his work—learning opportunities—but often they’re not. Teachers don’t choose who they collaborate with; their partners in education—their collaborators in this ‘art’—are assigned.

And at the end of the day, what outcome of teaching is the artistic product? Is it the students’ worksheets, exams, or papers? Their projects? Themselves? Does a classroom or a test score resemble a painting? A play? A statue or piece of pottery? A novel, poem, or piece of music? Surely the art teacher, choir teacher, band director, and drama instructor produce students who create art. But is it art when my students in English read something and articulate how its main point is developed? Is it art when my students, by way of my instruction, raise their ACT scores? When they become better readers or collaborators? How about when they merely get on task, do what they are supposed to do, and we meet our goals for the day—and then do so again and again, day-in and day-out, for an entire school year, with the manifold breaks and interruptions an entire school year encompasses?

I must often be artful in working around problems—in dealing with unexpected interruptions, in coming up with new ways of explaining concepts when my primary and secondary routes to explanation don’t work—but I’m not sure that what I produce is art, and I don’t think that my way of behaving in the classroom is as akin to that of an artist as some may think. (As a novelist, I am a practicing artist, and know what it is to produce art. The activity I conduct in my classroom is very different. At best, you could say that teaching is a performance art, during which the educator plays the role of teacher for their students—but, no, this isn’t true. One may playact teaching for awhile at the beginning of their career as they ‘fake it until they make it,’ but the best teachers are authentic—they bring forth the true teacher within themselves when faced with a classroom of students.)

Business:

Based on the language I’ve heard most often during professional conferences, in-services, and consultant visits in the nearly two decades of my teaching career, it’s apparent that the field of education desperately wishes that it was a business. We would love our product to be standardized and reproducible; our students to be clientele; our choices to be data-driven. More than anything, we’d love to be able to point to an improving bottom line.

But education isn’t—cannot be—a business. At least public education cannot.

Here are some things I know about businesses:

Businesses benefit when they niche down to serve specific customers with specific needs. No business is successful in trying to cater to everyone.

Businesses can fire their workers when they are dissatisfied with them.

Businesses can ‘fire’ their clients by deciding not to work with them.

The animating force that drives most businesses is their desire for monetary profit—a ‘healthy bottom line.’

And in education we cannot niche down to serve specific customers with specific needs. We must teach all who come to us. We must try to cater to everyone. Unless a student assaults another student or does drugs in the building, we cannot ‘fire’ our students (who are both our workers and our clients, both collaborating with us to create their educations and consuming the ‘good’ of the educations we collaborate on creating). And in education, it turns out that ‘a healthy bottom line’ is incredibly difficult to choose, forget about measure. Is the bottom line test scores? Graduation rates? Rates of university enrollment or professional employment three or four years after graduation? How low rates of depression, anxiety, teen drug abuse, or teen pregnancy are? We have settled—unfortunately—on test scores and graduation rates, which turn out to be relatively easy to measure—and relatively easy to manipulate. I’m not sure either is truly indicative of real learning or future success, either.

From bad to worse: if schools are to be businesses, then they must be big businesses—and big businesses grow to include robust, even bloated, middle management apparatuses. This bureaucracy ‘helps’ improve productivity on paper, often by narrowing goals to pursue efficiency ruthlessly. Darkly, they fudge numbers, and also function as insulating layers between the top and bottom of educational organizations—schools—to prevent communication, rather than facilitate it; to enable downward, profit-seeking (read: test score and graduation rate-inflating) pressure no matter the means; and to provide the ability to plausibly deny topside knowledge of bottom-side methods and problems should the ‘means’ turn out to be inappropriate.

Beyond the large problems associated with saddling education with unhealthy bureaucracies, chief among the problems with the ‘business’ model of education is that, similar to the scientific approach described above, it reduces and narrows in pursuit of its goal (profits/ test scores) at a time when clientele students—children, adolescents, and young adults—ought be treated to broad educations and experiences in preparation for their lives. Often, this narrowing is enforced punitively, when these young people need all the generosity and charity we can give them.

Craft:

So if teaching isn’t a science, art, or business, what is it?

It’s a craft.

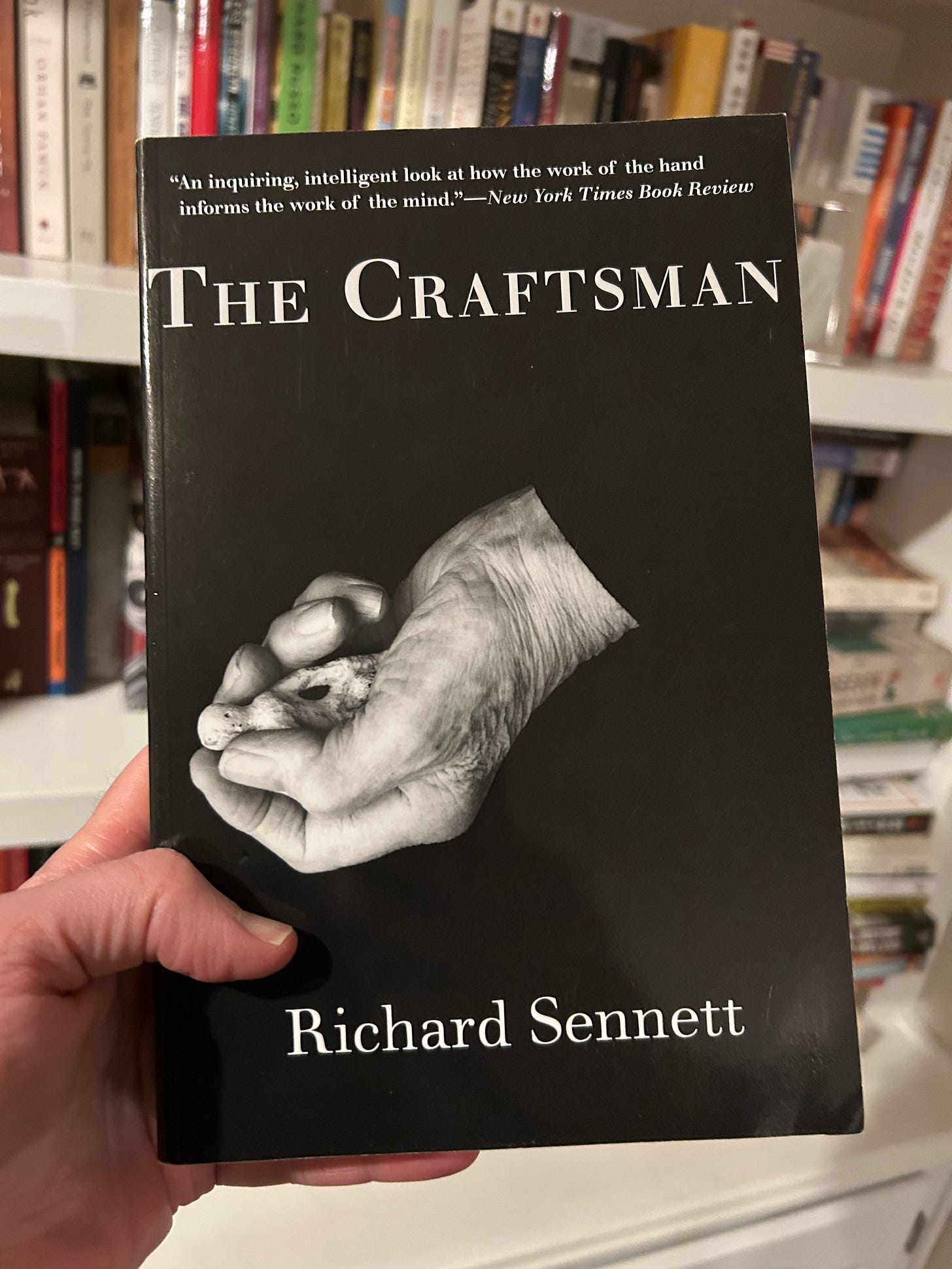

For much of my career, I was firmly in the ‘teaching is an art’ camp, casually overlooking the ways the ‘canvas’ of my classroom occasionally looked like a crowded artist’s studio, but seldom appeared to be a finished or even half-finished work. I’ve now moved solidly to the ‘teaching is a craft’ position. It wasn’t until I read Richard Sennett’s book The Craftsman that I began to appreciate that what I was doing, art-adjacent, was actually craft work.

Consider the humble craftsperson: painter not of canvases, but the outsides of houses or insides of office buildings. The craftsperson is hired and shows up to do a job; they bring with them their equipment, experience, and expertise. They do not choose the parameters of their work—they set neither range nor limits—but have their parameters assigned. Given this assignment, they must use the tools and expertise they have—often getting creative, occasionally thinking outside the box—to finish the job to the best of their abilities. The craftsperson doesn’t do a uniform job—they don’t produce a uniform product—but they always do the best they can with what they are given. The single-story house they paint on Monday and Tuesday is nothing like the three-story house they will paint on Wednesday and Thursday. The latter requires taller ladders, will require rotting wood to be replaced, has more eves and unexpected corners. Their specialized abilities allow them to size up their task, determine the best way to approach it, deal with unexpected hurdles along the way, and finish far more quickly and efficiently—and far better—than a layperson ever could do. At the end of the day they earn their wage and have, perhaps not a museum-worthy work of art (if only because our museums are mostly reserved for our ‘high’ art), but the satisfaction and pride taken in a job well done. Ask a craftsperson for insight into the work they do, and they will share their knowledge eagerly, always demonstrating nuances and complexities the lay person would never consider. A conversation with a craftsperson will always demonstrate that jobs that look simple on the surface are, in fact, made up of manifold decisions that only the true connoisseur of the craft would ever consider.

The teacher, like the craftsperson, is undervalued. Like other craftspeople, teachers do necessary tasks and are taken for granted, under-appreciated and underpaid. Like the true craftsperson, downward administrative and supervisory ‘help’ or pressure on the teacher are most often unhelpful. As the teacher is the true expert in the field, administrators—to say nothing of legislators—seldom truly know anything about the job the teacher is doing. Though many administrators in education are former teachers, those administrators can only truly offer help to neophyte teachers and teachers who belong to the subject areas they, the administrators, once taught. Then, too, truly good teachers often stay in the classroom, and there’s a too-common and pernicious tendency for bad teachers to leave the classroom by ‘failing up’ through the administrative escape hatch.

As a teacher, year-in, year-out, I’m presented with my courses, my curricula, and my students. If I have six sections of a particular class, each section will have its own personality. The discussion over a prompt I have with my first block on an ‘even’ day won’t work out the same way the discussion will on third block on my ‘odd’ schedule. Approaches to instructing, motivating, or correcting behaviors that work with student ‘a’ will seldom work the same with student ‘b.’ Unexpected distractions will come up—snow days, sick days, fire drills, assemblies, a pandemic. My class will be shortened, lengthened, a student will transfer in, we will move to remote learning. Students will demonstrate deficiencies in reading, in writing, in social or attending skills. They will be dyslexic, bipolar, sleep-deprived, anxious. Depressed, anorexic, self-harming, or merely going through some things at home. As a teacher, the job calls for me to show up day after day, bring my equipment, experience, expertise: to consider every class differently, every student differently. Navigate government, administrative, parent, and student needs and expectations—an order that is the reverse of what it should be.

Understanding teaching as a craft throws light on the troubles of early-career teachers. Having finished their undergraduate degrees, new teachers aren’t equipped with the “scientific knowledge” necessary to solve all of their classroom dilemmas—or even really teach their students. If they have been given the false impression that they are equipped, then they are about to learn the error of their beliefs in a very painful manner. The forgotten truth is that a bachelor degree, of course, means that one is a neophyte in an area. The term bachelor is closely akin to a helpful craftsman’s term: apprentice. Were we to recognize bachelor degree-holding teachers as apprentices, we might cut them some slack: give them access to mentors (as many districts do); assign them smaller classes; reduce our expectations that they be highly effective immediately. We might recognize the problem of having far too many apprentices and a dwindling number of ‘masters’ in our classrooms.

Understanding teaching as a craft also helps throw light on the problems with the ‘teaching-as-a-business’ approach to education. To understand education as a business, an enterprise measurable by a ‘bottom line’ (again: which line?), is to assume that a teacher is some kind of simple functionary—a cog in a machine, easily trained, easily replaced. That the job being done is merely one of presentation, supervision, management, administration, or accounting, and not a craft, as painstakingly learned and difficult to do as any art.

Craft takes time and effort to learn. Craft workers need the time, space, freedom, and respect to apply their expertise. They must be given the permission and forbearance to try new approaches and to fail. Classroom teachers cannot expertly ply their trade when students are herded through their rooms like cattle, efficiency-minded business-bureaucrats expecting teachers to use the magic ‘science’ of pedagogy to educate them all quickly and effectively no matter their numbers or situations to prepare them for the real world. Teachers-as-craftspeople cannot develop without mentorship from other teachers, without freedom from overbearing and prescriptive administrative oversight, without the freedom to use the best of their own learned judgement.

In looking back over what I’ve written, I see that a common theme runs through my thoughts, especially with ‘scientific’ and ‘business’ approaches to education: that they’re reductive, and leash students and teachers when our young people and their educators ought to be roaming widely together. The craftperson’s impulse is to fit and improve; the consultant class brought in to ‘fix’ education in the last few decades have worked to curb these generous impulses in favor of a narrowing standardization that has had negative consequences for us all.

Finally: I fear I may have disappointed some of those with a romantic notion of teaching by calling the profession a craft rather than an art. This need not be the case. Crafts and craftspeople should be more highly esteemed and celebrated in our culture than they currently are. As all true artists knows, art begins in craft. In closing, I’ll share a few lines by a particularly generous artist: the last stanza of Marge Piercy’s poem To Be of Use, one of the poems I always share with my seniors to end my school year; one of my favorite poems ever since I first read it seventeen years ago:

The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust.

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real. At the risk of over-explaining: this is what teachers and other craftspeople bring to the world: common work, worth doing, well done. Common work, well done, worthy of museum-caliber veneration.

My novel Why Teach? is now available in paperback and e-reader editions from Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo. If you haven’t picked up a copy yet, I hope you’ll do so—it offers keen insight into what life as a young teacher was like during NCLB, and it boasts a moving plot. Positive Substack book reviews are available from Scott Spires’s The Lakefront Review of Books and Isaac Kolding’s Amateur Criticism.

If you enjoyed the above essay on education, you may enjoy my teacherly short stories “Cheaters” and “The Troubles of Mariel Clement,” or my bookish poem “Forests, Trees.”

Wonderful, reflective piece.

I have a very similar sense of how teaching is situated as labor/activity with the only slight difference being that I think of it as a "practice," which I define as the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and habits of mind of a practitioner. (I refer to writing as a practice as well, and really, it's a lens that can be applied to any labor/activity.)

As you illustrate here, I think one of the key parts of a practice/craft is the necessity of experience as a way to practice the practice. There's really no substitute for it.

I appreciate your insightful reflections. I agree, not a science, not an art, not a business; although, there are elements of each of these in teaching.

I'm still a fan of 'gardener', as per Fröbel's kindergarten. I think it best describes the care and nurturing of life (although, I am quite far removed from Fröbel's model). However, I do feel that one must love gardening to fully relate to the richness of the metaphor.