Notes on a Toxic Pedagogy

“Pedagogy” is the science of teaching. It makes an awful lot of sense for k-12 teachers to study the science of teaching: we want our students to learn, after all, don’t we?

It also makes sense for other organizations—say businesses, the US military, or the FAA, for example—to think carefully about pedagogy. If a business wants to produce a high achieving sales staff, it likely needs to train them. The US military, of course, renowned for the efficacy of its fighting forces, is renowned for the rigors and efficacy of its training. Do you think the people who train air traffic controllers and run airports in the Unites States know some things about pedagogy? I can assure you, they do.

Here’s a basic pedagogical framework widely used in k-12 education and in many organizations that exist outside it today: you pretest to see what your pupils know or are capable of doing, you start your training from the baseline you find there, you begin delivering instruction and continuously assess along the way to see how your pupils are progressing, and you put in a final assessment—a “summative” assessment—at the end of the training to see how they have done.

Training like this makes an awful lot of sense for groups with clear, measurable goals and constituencies who’ve signed on in hopes of achieving those goals. I think they make less sense, believe it or not, in a number of k-12 classrooms. In fact, I’ve come to think of the rigid, formal adherence to this kind of program of study as counterproductive—even abhorrent1.

Let’s get semantic and talk about words. The one I used above the most often wasn’t teaching, it was training. Training is something you can do when you have simple, repeatable, discrete skills you want to establish and refine. Teaching, as we do (or should do) in k-12 education, is something bigger and broader. We’re in the business—or should be—of preparing students to grow up and become adults. We’re inculcating them into our diverse and multifaceted culture. We’re preparing them to participate in a complex and multifaceted democracy. We’re getting them ready for workplaces that are, in many cases, rapidly changing, and in others, not even in existence yet. We’re in the business of developing human beings.

It’s kind of a tall order.

Let’s go back to those soldiers and business-going worker bees I mentioned above—or any of the other professions whose work in ‘measurable’ fields results in them being touted as paragons to k-12 educators—those in the medical profession, say, whose standardization has saved so many lives. Without exception, all of the workers in these industries applied for their jobs. They want to do them, and are compensated, with bi-weekly or monthly paychecks, for doing them. Their continued employment, to say nothing of their potential for annual raises, is predicated on their doing their jobs well. And—just to reiterate—they wanted to do these jobs and presumably take pride in doing them well. They are intrinsically motivated to excel.

For people in these positions, clear, measurable goals and tight feedback loops are powerful and effective. But consider the application of this model to k-12 education. In kindergarten we might measure students’ understandings of colors, shapes, numbers, and the alphabet in a baseline test, then work to help them grow throughout the year. Everyone can agree these are important skills for all students to learn; kindergartners, in general, are pliable and eager to please their teachers. Things begin to get pretty murky pretty fast after this, though. Are we sure what knowledge our students all need to learn at every grade level after that? (We understand that students are typically “learning to read,” until third grade, and then “reading to learn” in subsequent grades, and so it makes sense to monitor their progress, target students who fall behind by giving them remedial lessons, and, as Mississippi and many other states have done, hold students back when it is clear they are not ready for fourth grade.2)

With all of the manifold strengths, weaknesses, interests, personalities, backgrounds, cultures, home situations, goals, and dreams that our students bring to our classrooms, though, are we sure we can standardize what education every child needs? If we could, would we want to? If education was entirely about equipping students with knowable, discrete skills, then standardization would make sense—but equipping students with discrete skills isn’t teaching, it’s training. Teaching is broader and more varied. It’s looking for potentials in students and developing those potentials. It’s taking a class of twenty-eight students and preparing them for twenty-eight different paths in life. It’s modeling how to be in the face of questions, problems, hardships, and vicissitudes.

If I’m training my students by teaching Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, then I’m training them to understand structure, conduct close readings, notice foreshadowing, look for juxtapositions and character foils, identify subjects and themes, search for evidence that supports their arguments about subjects and themes—etc. And I am training them when I teach Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. But I’m also teaching them, and things get a little looser there. Different kids are walking into the book from different places and walking out with different understandings. Almost all of them will be better readers when they are finished. In some explicit ways that I have taught, they’ll have learned some pattern-recognition and vocab. In less explicit ways, they’ll have become faster readers, picked up vocab I haven’t taught, and have developed little reading schemas too small and specific for me to have explicitly taught. I’m not teaching for “mastery” (how could one “master” Shelley’s novel Frankenstein?); rather, I’m telling my students that “We’re shooting for an 80% understanding.” Many of my students won’t reach this hypothetical level. Several will. Some will maybe touch 85 or 90% understanding in this fictitious world in which we can quantify our understandings of a novel. Some students will only get 50 or 60%—and that’s okay! If all of my students are on a continuum as readers, they will each have advanced along that continuum by reading the book. What’s more, they’ll have learned some contexts and lessons—understanding and frameworks within which and with which to make use of their “skills”—that they can apply later in their lives, or even now.

Like what, Mr. Shull? What important “contexts and lessons” can students today in 2025 learn from Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel?

I’m glad you asked.

For one, they can learn about Romanticism and the ways it was a push-back against “The age of reason,” the tyrannies of institutions, and the cold inadequacies of empirical knowledge. In our current age, with our current backlash against institutions and the cold inadequacies of empirical knowledge (indeed, in this essay in which I argue against the cold inadequacies of empirical knowledge), these ideas are relevant and worth discussing.3

For another, students can think about the importance of companionship in our lives—can consider the monomaniacal, self-isolating Victor Frankenstein, who put distance between himself and his family, as opposed to The Monster, who would have done just about anything to sit in a room with a roof, a dry floor, and a fireplace at the end of the day and just listen to people talk and be part of their crowd.

For third, fourth, and fifth reasons, they can think about the dangers of ambition, unchecked scientific advancement, and the pursuit of revenge.

Sixth: how about the importance of spending time in nature—“touching grass”—and seeking out the soul-expanding and perspective-correcting powers of the sublime as a cure for the busynesses of our lives and minds?

Seventh: want to talk about empathy? The lives of the othered who are othered merely because they look different? Here we go.

I could go on, but I think you get my point.

There are reasons the founding fathers wanted a literate society, and there are reasons that public education has long been deemed a public good in our country. The essential “goods” of public education go beyond mere workplace or academic-place readiness. A skills-based education doesn’t do much to prepare students for their civic or personal adult lives—doesn’t prepare them to be thoughtful members of a democracy or responsible individuals who are occupants and stewards of our planet at this specific and important point in our history’s timeline.

So back to that tight pedagogical cycle of pre-assessment, assessment-as-we-go, and summative ‘final’ assessment. What does that look like in the k-12 school system?

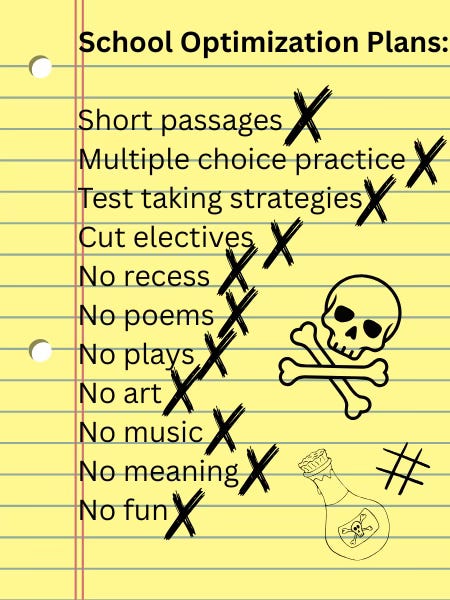

For one thing, to enact it, we have to narrow the curriculum4 and decide what the “essential skills” are.

For a second, teachers must align with one another to make sure everyone learns the same skills at the same time.5

For a third, teachers must take time that we don’t have to a) agree on the essential standards, b) create standardized assessments for them, c) spend time together analyzing the results of these assessments (the data), and d) take time to re-teach and remediate students who haven’t learned what has been deemed “essential.”

I suspect some of my readers might not think this sounds so bad, but, frankly, a lot of ideas sound good on paper and fall apart in practice. In practice, after basic and fundamental skills are learned, it becomes inordinately difficult to determine what skills in the curriculum are “essential.” In truth: they all are, and none of them are. In my English classroom, I offer a buffet of lessons that my students may partake of; I work hard to impress upon my students the importance of said lessons, and certainly have a few concepts and ideas I elevate above all else, but, to paraphrase the poet Taylor Mali, we give students what they need before they know they need it—and it can be difficult to make all of the lessons stick.6

In addition, it turns out that teachers aren’t always the best assessment builders. While we have some training in assessment, our primary talents are in teaching and managing classrooms. Give most of the teachers I know clear objectives, and they will achieve them. Ask those teachers to create valid and reliable assessments and my confidence falls off pretty fast. For an assessment to be valid and reliable it needs to pass a pretty high bar. When you ask teachers to design and administer their own assessments for students—assessments that they, themselves, are partially evaluated on… well, motivations can become confused and things can get murky. (No need to even get into the motivations of people whose entire jobs are assessments and the presentation of data…) If a district decides to pay for proprietary assessments—well, there seem to be a lot out there, and I’m a little dubious about their reliability and validity in a number of cases, and schools, frankly, are drowning in data already: teachers and administrators may have access to hundreds of pieces of data in the forms of grades, standardized test scores, and student and parent surveys by the time a student is in the eleventh grade. It’s literally more data than we can use.

On the matter of that data: 1) for emphasis: we couldn’t use all we already have if we wanted to, 2) if we wanted to use it, we would need to be pretty skeptical of the data we have because of the number of variables that can skew assessment results, and 3) we don’t need most of our data to teach our classes, anyway.

I don’t teach my students argumentative writing or vocabulary, grammar, and punctuation rules every year, year after year, because their formative assessment data tells me they need to learn it; I teach it because I know they don’t have the skills coming into my classroom7. Granted, some of them do have the skills and are more proficient than others—and some of them certainly don’t, and are further behind than others—but I teach it all to them, anyway, and the best students get a little bit sharper and the worst make the biggest gains. You might argue that this is an inefficient use of my class time, which would be fine. I could counter by arguing that administering a formative assessment to get data I largely already ‘have,’ anyway, is a worse use of my time.

If the use of time—the optimization of time—is largely what this whole ‘data-driven instruction’ thing is about—and I think in many ways it is—then I don’t want to have anything to do with it. I don’t want to optimize time or education. I’d like things to be sub-optimal. Sub-optimal, I happen to think, is actually the optimal place to be in the classroom and most places outside it. I want to move forward at a manageable rate; I want my students to be able to lose focus during a class period—and during a ‘unit’ of class periods—and then regain it. I want them to get different things from Frankenstein if they are going into Political Science, Computer Science, Sociology, or someday plan on becoming a parent. If they ‘achieve mastery’ faster than other students, I don’t want to give them more work—I suspect they have other interests that occupy their minds. My students may be thinking about their upcoming debate competitions, soccer games, robotics ‘build seasons,’ theater ‘show weeks,’ or just daydreaming. I want them to have five or ten minutes of ‘dead time’ at the end of my 85-minutes class—though we don’t always—after we have accomplished our goals for the day, so that they can talk to one another face to face and be high schoolers.

Speaking of optimization, there isn’t much that is less optimal than the enormous bureaucratic appendage of testing administrators, instructional coaches, and “curriculum specialists” that public schools have been burdened with in the last quarter century. By one measurement, administration increased 88% between 2000 and 2024, while student and teacher numbers increased by a mere 8%. This may be in part a response to “behavior problems,” but is certainly in larger part due to the tremendous logistical requirements of administering so many more tests, ‘aligning’ curricula, and tracking data. (I would also argue that when students are forced to do tedious, redundant “skills-building” work day after day, month after month, year after year, their inclinations to bridle and cause behavior problems increase.) …Certainly, we haven’t seen anywhere near an 88% increase in student outcomes as a return on our investment in administration.

Speaking of the students, are they better off for being treated to this regimen of tightly organized loops of assessment and explicit instruction? Do a thought experiment: would you enjoy it and benefit?

Imagine you come into a classroom ready to learn. Before the teacher teaches you anything, you’re tested. You get the results and find out that you’re not very smart—bummer. Then the teacher starts teaching, and as she goes, she keeps administering little tests. You’re not ready for the tests—they’re coming at you too fast—and some of them, many, seem… well, elementary. Others feel outright arbitrary. If the scores are going in the grade book, they’re hurting your grade (which you have become preoccupied with; you’ve long since learned that your grade determines your future, and you’re learning for the sake of your grades—or jumping through the hoops, at least—an extrinsic motivation, instead of learning because you’re a human being with human curiosity who wants to learn, an intrinsic motivation), and if your teacher is giving you the assessments but not putting them into the grade book—if he or she says they are ‘just collecting data to guide instruction’—well, you’ve become tired of that game. You’ve been doing it, after all, for more than a decade by the time you hit eleventh grade, and this school thing hasn’t turned out to be what you thought it might be. You wanted to understand the big, strange, complex world; you wanted to sample some electives to explore your talents; you wanted to learn about history and art and culture and biology, math, chemistry, physics, and literature and find your place in the world, but you haven’t. Your classes have all seemed, well, rote and stupid. They never took off; never stretched their legs—right when things were getting interesting you often stopped to take a break and assess, and in that assessment you were judged and found lacking. And why bother with that?8 Why bother with a system of stupid multiple choice assessments where you’re judged arbitrarily and exhaustively in classes that have been stripped down to “essential standards,” where teachers who were once passionate about a subject have been reduced to training students to pass tests instead of teaching them to explore, problem-solve, and flourish in a landscape of ideas?

This type of education isn’t only tedious, it’s demoralizing. The highly-motivated adult business person or would-be Navy SEAL can deal with setbacks when they are assessed and found lacking. The young person who doesn’t know what they want to do in the world, who isn’t sure if they are even interested in math or science or English or history—they’re apt to just quit, or develop a series of coping mechanisms such as regularly short-cutting, bullshitting, and cheating to get by.

And yet we not only persist in this direction, but are accelerating. Why? Who benefits? Student achievement in the last two decades is stagnant at best. Teacher burnout is tremendously high—people are leaving the profession in droves. The only ones who are really benefiting are the legislators, administrators, and academic data wonks. When we narrow curricula and drill to pass tests, we don’t better prepare students for their lives, but we can produce mirages of data that make it look like things are improving. Legislators who mandate narrower curricula can point to their state’s high test scores with pride, potentially attract businesses, and win reelections. Superintendents can keep their jobs. Principals can apply for positions as superintendents (or associate superintendents—the positions are multiplying). Academics get more data to sift in their offices far from real classrooms. Certainly wealthy suburbs competing for wealthy tax bases enjoy good-looking statistics9. On the other side of the coin, during No Child Left Behind, failing schools had to narrow their curricula to pass state tests or lose funding. Inexperienced and ineffective teachers, perhaps, can be propped up by requirements that narrow and standardize instruction, but it seems to me that it comes at the cost of strong, experienced, and inspirational teachers being driven from the profession. Is this narrowing and standardizing ultimately good for the kids? The profession? Our society?10

I ought not merely criticize. I ought, of course, to offer my own solution: a vision of what I think education ought to be. I will, and I’m sure it will knock your socks off. Let teachers use their educations and teach. Let them cultivate their skills and grow as educators in their classrooms. Let them teach broadly and deeply as they see fit. Let them assess, and let assessment guide some of their instruction, but deemphasize assessment. Stop training students to be specialists in this field of assessment-taking which, as far as I can tell, is not a field many of them want to pursue in their futures. Reduce the pressures on teachers and students. Let kids fail. Provide supports and alternative routes for kids who do fail. Stop scapegoating society’s problems on a ‘failing education system’ and recognize that the failing education system is a canary in the coal mine for a failing society. Fund teaching, not a superfluity of administration. Begin dismantling the paralyzing scaffolding of ‘support’ that puts teachers in straightjackets and prevents them from doing the difficult work of running their classrooms, meeting their students where they are, and equipping young people with the skills, contexts, and understandings they will need in the world.

Perhaps my readers would like some business jargon to help this proposal of mine go down more easily. I offer you lead indicators. Lead indicators are measurable indicators that can precipitate good lag indicators. Lag indicators are outcomes. Think: basketball players who practice more (lead indicator) win more games (lag indicator). Lag indicators for school are students going on to college (and not dropping out in the first few semesters) or successfully entering the workplace. They are young people enjoying good mental health, individuals finding their places in the world, and societies thriving. Obsession with data and assessment has taken time away that we could have put toward effective lead indicators: students reading more, students writing more, students receiving instruction and taking notes; students speaking with peers and collaborating with others.

I have six sections of advanced placement seniors this year—roughly one hundred and fifty students I’m helping prepare for college and life. Each section has its own personality, and I teach all six of them in slightly different ways. Each has different needs, and I respond to those needs accordingly. I didn’t give any of them a formal ‘formative’ writing assessment this year. In the first nine weeks, in fact, beyond basic reading quizzes and a requirement that they complete a portfolio of short application and scholarship essays, I hardly ‘formally’ assessed them at all. I subscribe to Stephen Krashen’s maxim that a flood of input must precede a trickle of output. My students have grades in the book and have done significant readings and writings, but rather than assign numerical values to their work, I’ve largely just given feedback. We’ve read novels, short stories, essays, and poems—we have more of each of these, plus a few plays, still, to come—and we have treated them as playgrounds, models, substrates, and catalysts. Because I have written this essay against exhaustive evaluation, does that mean I’m not in favor of evaluating my students? Not at all! I’m assessing them regularly—daily—by their participation, class discussions, and writings. I keep these assessments informal rather than formal, and have cultivated a low-stakes atmosphere in which my students feel free to play with texts and ideas free of judgement. By assessing less and prolonging the stretches of time between my students being judged (and therefore, too often in their minds, defined), I’ve encouraged them to play with the texts longer and experiment with them in different ways—I’ve given them more time to challenge themselves and grow—have refrained from visiting the educational “offramp” that assessment too often becomes. It’s a strategy I used last year as well. My lag results? My “summative” data at the end of the year? After getting off of the hamster wheel of too much assessment and criticism, the papers my students wrote and the AP test scores they earned were among the best of my career.

Peter Shull is a novelist and short story writer. His novel Why Teach?, a story of youth, education, bureaucratic absurdity, and hope, has been called “A quintessential novel of the No Child Left Behind era” and “A supreme twenty-first century coming-of-age tale set in a swath of America referenced often but seldom truly examined.” The first chapter is available to preview here on Substack, and the book is available for purchase at Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo.

It should go without saying at this point that my opinions are my own, personal opinions, and not representative of my workplace.

Three notes, here:

a) As a teacher who once worked in a school that achieved a “miraculous” improvement in standardized test scores, I’m highly dubious of the so-called “Mississippi Miracle,” which seems to have been accomplished 1) by holding more students back (which I agree with), 2) by making use of ‘science-based’ phonics reading instruction (which I agree with), and 3) my surmise: by putting enormous amounts of pressure on teachers and students to pass baseline reading tests (which I disagree with). The story is that the ‘science of learning’ turned things around, but I suspect other factors played a disproportionate role. There are plenty of red flags here, perhaps the most notable of which is the large diminishment of gains by the 8th grade. There are many people extolling this “miracle” whose essays, should be read, but many of them seem to be associated with monied and ideologically-aligned think tanks, and I think skeptics and their perspectives should also be considered. I liked this one, for example.

b) I do believe in holding students back in early grades when they are behind, and I do believe in holding students back in later grades when they fail to meet standards and pass classes. In the upper grades, in particular, failure is a powerful lesson that a number of young people could stand to deal with in the relative safety of the school system; as things stand now, social promotion and powerful pressures to increase graduation rates have ‘protected’ students from failing in middle schools and high schools, depriving them of powerful learning experiences, providing many students with false senses of their own competency, forcing many districts and schools to water-down expectations for classes, and causing a general erosion in a belief in the institution of k-12 education.

c) I, myself, was held back in grade school. My parents still praise the wisened educator who looked them in the eye and told them I wasn’t ready for third grade. I went from being one of the youngest and most immature students in the classroom to being one of the oldest, and I certainly benefited from the experience.

There are people on this platform and elsewhere arguing, for good reason and with good evidence, that we’re entering a new age of Romanticism.

I’m not sure that a lay person always understands what ‘narrowing the curriculum’ means. In a classroom context, it generally means making cuts of longer, more difficult, or more complex material and activities that are deemed merely ‘fun’ or ‘community building.’ On a larger “building” level, it can mean the removal of the elective classes like art, music, shop classes, computer classes, and the like.

Counselors shift different students to different teachers for various reasons. Some teachers have more SPED certifications, others are better trained to work with ESL students. Some young men work better with male teachers; some young women do better in rooms headed by women. Some teachers are slated with more students who have known behavior issues. Some teachers are better with high achieving students; sometimes a counselor just feels like ‘so-and-so will be a better fit with Ms. X.” When the schedule is largely defined by when certain classes are offered, sections get ‘slated.’ The band kids end up in the same math class. The calc kids end up in the same English class. The AP Physics kids largely move as a block between all of their classes because they also share AP Chem and these classes have limited offerings… and so different classes have differing personalities and ‘centers of gravity' in terms of ability. Then, too, morning classes are simply different from afternoon classes, and can require different approaches…

This isn’t a fault of the curriculum or my fellow teachers: the students have been taught the material—or much of it, anyway—they just haven’t retained it. Perhaps because they only learned it long enough to take a quick formal or summative assessment? To teach English is to go over the same, similar, and analogous subjects year after year piling up small understandings, the students getting a little smarter and retaining a little more with each repetition and new experience.

One of the most damning things about education as it is practiced today is the fact that so few students now want to pursue teaching as a career after experiencing it the way we have administered it in the last two decades. I can’t say I blame them.

Show me an “award winning” school district, and I’ll immediately suspect 1) a wealthy tax base, and 2) a narrowed, test-prep curriculum. How’s the kids’ mental health in that pressure cooker? Paradoxically, a number of students are receiving broader, richer educations in school districts that haven’t jumped on board to chase the shallow, glittering accolade of being the best in the state at standardized testing.

There are further consequences for this kind of ‘standards-and-mastery-driven education’ that I could highlight. When students are subject to so much ‘drilling’ and high-stakes testing that purports to assess (read: judge and define) them, their anxiety goes through the roof. All of this extrinsic pressure doesn’t promote individual flourishing, and I think there are arguments to be made that if this generation is particularly solipsistic, materialistic, and hopeless, it’s partially because of the near-vacuum of ideas and historical understandings they’ve grown up in during our shift to ‘skills-based’ curricula. People who are literate and have read literature have been equipped with contexts and ideas that help them understand and navigate their lives; when literacy is redefined merely as “the skills and ability to read” and literature is excised from the curriculum we miss opportunities to prepare our students in advance for the complex world we’re about to release them into.

Peter, this is such a fantastic piece! I have read and reread it throughout the day today, and you have beautifully explained my daily lived experience as an elementary school teacher. It has been such a long time since I've been in a teaching assignment where assessment wasn't emphasized (before NCLB), that I can hardly remember what it was like. I do remember reading more books and being more present in my students' academic lives because we had the time to teach the whole child, not just the test-taking part. Did we have tests? Yep! But we learned from them, made adjustments, and then moved on. The thing I miss the most was the slower pace.

"I want them to have five or ten minutes of ‘dead time’ at the end of my 85-minutes class—though we don’t always—after we have accomplished our goals for the day, so that they can talk to one another face to face and be high schoolers." Yes to this. And yes to everything else in this masterpiece, Peter. (And love the Jerry Maguire idea mentioned below by Adrian!) Definitely plan on sharing this with other colleagues and friends at my own school. Bless you.