Chasing the Highly Productive Day

Reflections on daily work, breakthroughs, the 'grindset,' and writing novels

Introduction: Chasing the HPD

It’s almost the end of May now. The school year is coming to a close, and I’ll be switching from my ‘teacher mode’ to my ‘writer mode’ for the summer. I’ll have eleven weeks—seventy-seven days1—of lessened responsibility to get my writing in. Eleven weeks’ time off sounds like a lot—and it is!—but it’s never as much as I need. I’m a novelist; I’d like nothing more than and uninterrupted stretch of four or six months—or eight or twelve—or every month for the rest of my life—to devote to my fiction.

I’ve done this enough times now to know exactly how the summer will go. On my first day off I won’t be able to write at all. Better courses of action will be to go to the gym, take a long walk, or shut down completely. I should make myself a big breakfast, get take-out for lunch, and watch stand-up comedy or trash television on streaming television through the afternoon, cleaning up the messy nest I’ve made for myself on the couch before my wife gets home at five-thirty.2

The second day I’ll be rested, contrite, and ready to write: contrite because I’ve wasted a day; ready to write because, even as I’ve wasted that day, I’ll also have spent it filling my well. I’ll go to the library, lay out a row of index cards like talismans across the top edge of a table, slip a pair of earplugs into my ears, and start writing. I’ll put in a couple hours, maybe three, and I’ll head home, two days down, seventy-five to go. If I was productive, I’ll have written two or three pages. Maybe four or five. It will go like this every day that I write for the rest of the summer: two pages or three—maybe four or five—some prose, some journaling, maybe some notecards or a sketch or diagram representing some aspect of my plot. But sometimes I won’t go home after two or three hours—sometimes I’ll stay for four or five. Or I will go home, but after lunch I’ll keep writing. I’ll rack up seven or eight pages, or nine or ten. When I’m finished, I’ll have not just good work to look back on, but breakthroughs: key sections of dialogue written, chapters wrapped up, and character arcs completed.I won’t have had a merely productive day (a few of which can yield a good draft of a short story; a few hundred of which can yield a novel), but a highly productive day.

The highly productive day—or HPD, as I’ve dubbed it in my notebooks—is, I think, every writer’s dream. It includes, almost invariably, the artist’s most highly-coveted sensation, better than satisfaction, accolade or adulation: flow state. Everything feels natural and automatic, as if God has parted the clouds and touched one’s brain with his forefinger; as if Shakespeare, Austen, Tolstoy, and Morrison had agreed, over coffee in heaven, to channel their energies to one lucky writer down on earth, and it was me.

With one novel published, another coming out in a few months, and a third I plan to release within the near-horizon of the next two or three years, I’ve been veteran of more than a few HPDs. Having experienced a number of them, I have some notes on this enviable experience to share.

Three ‘Ironclad’ Rules of an HPD:

I cannot have an HPD if I haven’t been working steadily already; an HPD never takes place on a first day of work; it only takes place after several consecutive days or even weeks.

Having achieved an HPD, it’s guaranteed the day that follows will be a disappointment—so much so, in fact, I’ve begun to think I might be better off taking the day off than even trying to write anything new.

The product of an HPD is never a final product. Though it’s often a breakthrough, it’s never so good that I don’t need to go back and clean it up or revise.

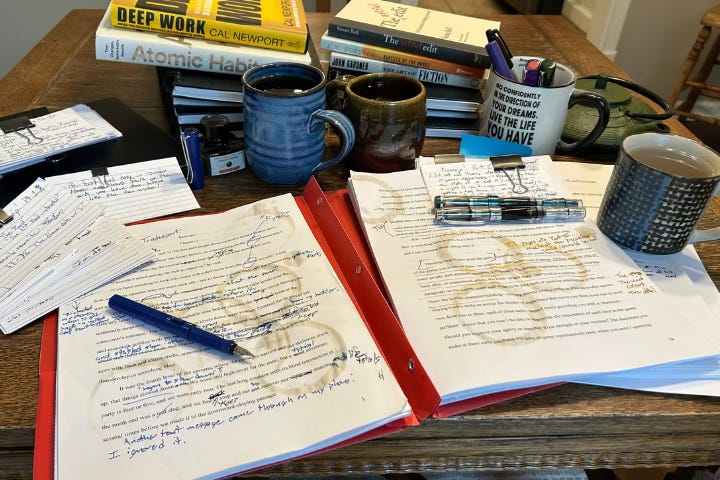

With regard to my first rule: an HPD always results at the conclusion of several days’ or weeks’ work. It’s the harvest of many hours’ thought. The ‘seeds’ planted during those hours of thought take many forms: they are drafted pages, journaled pages of writing about what I’m writing, and notecards I have dropped thoughts onto. The HPD blooms like my wife's roses are currently blooming in my backyard: the vine thickens, the bud emerges, the bud burgeons, and then the bloom springs into life3.

With regard to the second rule: I always experience a post-HPD letdown. I sit down the next day fully expecting the thoughts to flow as easily as they did during my HPD—I think, erroneously, that I’ve broken into a new, higher level of being—and I inevitably find that my metaphorical well is empty: there’s simply nothing in me to put on the page. The HPD has taken everything, and I’m not only empty but exhausted. I can try to ‘do the thing’—aspire to 90 minutes or 2 hours of work—two pages, or maybe 500 words, measures that seem to be standard writers’ measures of daily success, but it’s guaranteed to be particularly slow and unhappy going, and the pages are seldom of any real quality.

Third: The result of the HPD will need to be revised. The greatest gifts of the HPD will be the elation of having hit flow state and the fact that the narrative has been moved so far forward—that I am so much closer to the false finish line of a finished draft, at which point I can begin working on my revisions. (Revising, for what it’s worth, is a practice during which, if there is a flow state, it’s much different and, I think, less pleasurable than the flow of composition.)

Reflections on ‘The Grindset’:

As this is Substack, I suspect many of my readers are productivity nerds. I suspect that the elders among you, people my age and older, are veterans of Internet forums, early YouTube, and the world of self-help and productivity books. And as this isn’t only Substack, but Substack in America (sorry foreign readers), I suspect you know that it may say ‘In God We Trust’ on the dollar, but we worship that dollar, not God. Our productivity in pursuit of that dollar is our religion; whatever product we might create is our imagined salvation.

I was fortunate enough to enjoy a relatively privileged, comfortable, and structured childhood that, after my parents’ divorce, became a pretty unstructured, unsupervised, and laissez faire adolescence. The public high school education I received wasn’t rigorous, and in college I both achieved and failed at low enough levels to get by. I began to finally understand the ‘real world’—or our American ‘Grindset’ version of it—when I went back to my old high school and began teaching, gradually paying off the debts, monetary and otherwise, I had extravagantly accumulated so far in my life.

My first brushes with ‘Grindset’ productivity-thinking came innocently enough: that quote attributed to Aristotle we see so often on high school walls: We are what we repeatedly do; excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit. Then there was a John Dewey essay, “Habit and Will,” from a Great Books collection, which I assigned to my honors sophomores and paired with a “Habit and Will” project.4

I did my own “Habit and Will” project alongside my students that year: I set my alarm five minutes earlier every day until I was waking up just after five, and I worked on my writing for an hour every morning. From Dewey, it was the logical move to seeing what the internet had to say about habits and the creation of art, and there were other books: Art and Fear by Bayles and Orland, The War of Art by

, Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and The Tipping Point, The Paris Review Interviews Volumes I-IV, ’s two Daily Rituals: Artists at Work books5, James Clear’s Atomic Habits, and Cal Newport’s Deep Work.My favorite part of Newport’s book is about two-thirds of the way through and promotes using ‘visible scoreboards’ and measuring ‘lead indicators’: the latter being the small benchmarks which, when met day after day, result in long-term goals being achieved. But what ‘lead indicators’ and ‘process goals’ (as opposed to ‘outcome goals’) should a writer shoot for each day? One written page? Two? 500 words? 1,000? Should it not be words, but time that a writer measures? Should one clock an hour? Two? Four? More? Should one take days off, or aspire to continuous streaks of productive days? I have 77 days off in the summer, but with family obligations to meet and the prospect of the salt mines of another school year on the other side of it, 77 days can seem like a precious short period. I’ve known myself to begin feeling pressure at the beginning of May (I feel it now): the grains are slipping through the bottleneck in the hourglass: my summer isn’t here yet, and somehow it’s already almost over.

The Cost:

Two of my favorite works in the productivity genre are Mini Habits by Stephen Guise and Seth Godin’s The Dip. The first posits that taking advantage of “Mini Habits” lowers the barrier to your productivity, and that if you set yourself small goals you’re both a) more likely to meet them, thus building confidence, and b) more likely to keep doing work after you meet your ‘mini’ goal—because, of course, the hardest part of any task is getting started. The second book suggests that artists, makers, and creators fall into a ‘dip’—that it’s actually easy to to get started on a project, but hard to keep going: that the day-to-day slog wears people down. The Dip argues that the key to success isn’t necessarily getting started, but rather keeping going.

During the Covid lockdowns, I had a finished draft of a book I was then calling On Education but which I’ve now published under the title Why Teach?,6 and I was working on another project called Komojo!, a shorter, more straightforward novel. Then I started working on a third novel: something I tentatively called The Grid7. And while the world was shut down and everyone was anxious and tired and terrified (and an awful lot of other stuff was going down as well), I was teaching online classes and in-person classes, getting up in the night with my small children, trying to help out around the house, writing Komojo! during my mornings and The Grid in my afternoons, writing query letters to agents for On Education/ Why Teach? every night, squeezing in grading, pushing to get in one more page to, as James Clear might say, get 1% better, trying desperately to climb out of the dip I was in—and my back was seizing up from leaning over my computer and my handwritten pages, and I seemed to be developing tennis elbow, and my wrist began to ache, and that ache became a sharp pain, and after a few months I found myself in a situation in which picking up a pen to even sign my name afflicted me with excruciating, agonizing pain.

I tried to fight through it—to write through it—and tried even to teach myself to write left-handed, but the situation was untenable. I did some work with speech-to-text, but it wasn’t the same as writing my drafts out by hand, and typing was a little more tolerable, but hurt terribly as well. I thought I might have to take a few weeks off, which became a few months, which ultimately ended up being about two and a half years.8

Today: Steady Progress and Seasonality

Today, with my first book published, another near-finished, and a third about 40% of the way through, I still chase ‘lead indicators,’ but I’m wary of the Highly Productive Day. I think I more fully understand why Hemingway liked to pick up his pencil midway through a sentence knowing how that sentence would continue the next day. I’m not so much interested in high production now as sustainable production, and while I’d ideally like to get 90 minutes or two hours of work in every day, I’m nervous about days when I feel I can go longer. One of the things I did besides working myself into a state of brokenness during mid- and late-stage Covid was outrun my imagination. It’s true that ‘the muse visits when you sit down to work,’ but it’s also true that the muse visits when you’re out taking walks, taking your kids to the park, driving to work, teaching your classes, reading other books, and sleeping at night. When I tried to push out three or four—or five or six—or eight or ten—pages a day, day after day, the quality of my prose suffered, and some of the narrative decisions I made were bad. Because I was so intent on moving forward, I didn’t always take the time to reflect on whether or not the direction I was moving was a good one. I made mistakes besides hurting myself that also cost me months of work.

Today I believe in seasonality. There are times to get a lot of work done and times to fall fallow. I can’t work every day, but I can work most. The days I’m not ‘working,’ I’m still working. My ‘lead indicators’ now are Did I solve a narrative problem? and Did I move the narrative forward? This means that as little as a written paragraph can be a Highly Productive Day, and that going on a walk and thinking about my novel can be a ‘Highly Productive’ use of my time. So can taking my kids to the park, or the pool—outings during which I don’t think about my writing at all.

I’m middle-aged, now. I’ve got my 10,000 hours in. I know about art and fear. I've developed my ‘mini habits,’ I’ve studied the great texts on writing, and I’ve read many of the great fictions that have been written. If my youth is behind me and I have less time left in this life, I also know who I am, know how to write, and know what I want to accomplish. Most importantly, I’m happy with my slow, steady, and productive pace.

My novel Why Teach? is now available in paperback and e-reader editions from Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo. I’m honored to have been reviewed by Scott Spires’s The Lakefront Review of Books, Isaac Kolding’s Amateur Criticism, Alex Sorondo’s big reader bad grades, and Trey Hinkle’s That’s Absurd!—check these reviews out before buying if you like.

A few pictures of my wife’s roses:

I have a fraught relationship with my ~eleven weeks off. The time is often mentioned as part of the compensation package for teachers, and people who don’t teach often point to it as proof that teachers ‘have it easy’ and/or shouldn’t argue for more pay. This isn’t really the place for it—I probably ought to write another entire post—but as a brief rebuttal, the fact that so many teachers are leaving the profession—and so few people are going into it now—despite the summers off and ‘livable wage’ ought to be setting off alarms all over the place. [If I could footnote a footnote, I would add that the alarms have been going off, of course, like many others in our society, so loud and so long that we can’t hear them anymore.]

This is a hypothetical summer: how my summers used to go before I had children. Now I’ll be staying home with my two little boys. I’ll have time to write, of course—there will be their ‘screen time,’ our little (and often interrupted) blocks of ‘quiet time,’ and times my wife takes them out—as well as some evening writing—but there will be trips to playgrounds and parks, the zoo, the pool, errands to run, breakfasts and lunches to make, snacks to have, questions to answer, arguments and fights to break up, etc. etc. Still, of course: I’ll have more time—and a more free mind—for writing this summer than during my school year.

I’ve shared some pictures of my wife’s roses in bloom at the bottom of my essay. These roses are the result of two and three years’ work. She carefully tracked which parts of our yard received the most sun, measured how much sun they received, ordered and planted her preferred varieties that would grow in our region; planted, watered and fertilized them, and, during the winter, fought to keep them warm by strategically covering them with blankets during several sustained sub-zero freezes. Last year, one of them was 3/4 killed off in the freezes and didn’t bloom; this last winter she tended them all the more carefully. I hope the metaphor(s) between her literal garden and my ‘word gardens’ is/are somewhat evident.

This is a great assignment, which I have also given to ‘regular track’ kids: you start with the Aristotle quote, Dewey essay, and maybe Malcolm Gladwell’s “The 10,000 Hour Rule” or a James Clear Atomic Habits excerpts, then have students write proposals for habits they want to acquire, lose, or change, and then give them a timeframe—a month, say—during which they follow their proposed plans. There plans should include several discreet and particular steps, including ways they will reward themselves if successful and how they will correct themselves when they fall short. Then they will journal or blog about it, and then they write a report on the whole thing, including quotes from the aforementioned texts and their own journals and blogs. The most difficult habit for them to break when I was first doing this one fifteen years ago? Texting while driving. Today I suspect it would be scrolling Tik-tok.

Though I am a straight white man born into some comfort, I’d still argue that Currey’s second book, Women at Work, has been far more helpful for me and would likely be more helpful for most practicing writers of any gender, identity, or status today. The majority of the female artists in the book had to work harder and be more creative about carving out their time, and it’s been my experience that being a twenty-first century high school teacher, husband, and father is more closely akin to most of the experiences of the female artists in the second book than many of the male artists in the first (let’s not imagine that I’m suggesting a) I have it as hard as some women, b) that all of those men had the most tremendous privilege, or c) that many of those women didn’t enjoy some privileged positions of their own…).

Yes, it’s true that Why Teach? and On Education sound more like non-fiction titles than fiction, and that neither title is particularly grabbing to the broader literary reading community, but these were the most apt I could come up with for the book I wrote. On Education, my longtime working title, was partially an homage to Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, which I still love after five or six reads and recommend to every reader I meet.

Komojo! is about a young man who drops out of college to manage a copy store in his university town. By day he’s a mild-mannered manager, and at night he leads a world-famous online adventure gaming guild. The Grid is a novel I briefly describe as ‘the kind of book Jane Austen might have written if she was a man living in Western Kansas in the first fifteen years of our current century.’

Yes, I did seek the advice of my general practitioner, then a highly-regarded orthopedic surgeon who specialized in the hand, and ultimately an occupational therapist who specialized in the hand. What ultimately solved my problem was correcting the problems in my back. I had spent so much time hunched forward that a whole chain of things going from my neck, shoulder-blades, and upper-back had tightened and locked up, and the weak link in the chain where the pain registered was in my wrist. If anyone else is suffering from this kind of pain, I’m obviously not a medical professional, and you shouldn’t assume your issue is the same as mine, but I suggest jogging, swimming, using a rowing machine, doing Yoga, and doing these exercises from this guy I found on YouTube. After reading Colm Toibin’s The Master, I suspect Henry James suffered from a similar problem to the one I’ve had. (Just to reiterate: I’m not a medical professional: I'm just sharing my experience. Please don’t sue me.)

Happy Summer writing, brother. This captures the tension between ambition and sustainability with warmth and gentle and helpful advice and perspective.

I got so much out of Newport's Deep Work. It helped me see where and how to focus my time. Now when someone says they write ten hours a day (ahem, Murakami), I simply don't believe it. At least, I don't believe he's at the desk actually writing. He might be swimming-writing or walking-writing or babysitting-writing. Which is great! Not knocking it. Like you say, that is actually part of writing.