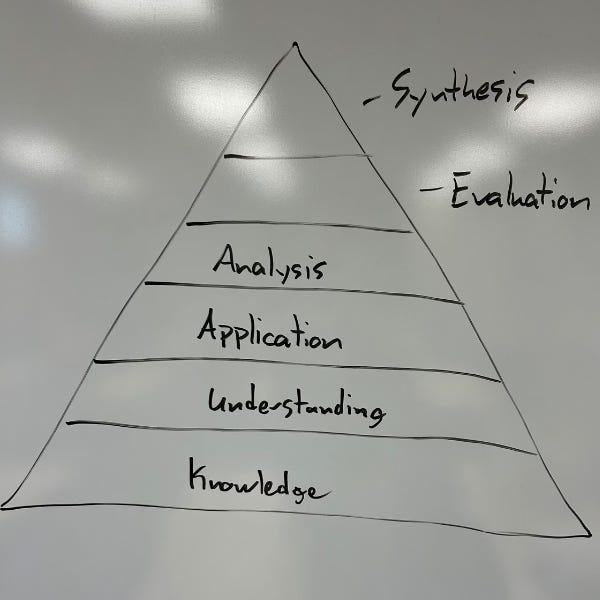

Bloom's Taxonomy

How an old framework can help us think about teaching today

Are you familiar with this triangle?

I first learned about Bloom’s Taxonomy in a psychology class when I was in high school. I didn’t think twice about memorizing and forgetting it for the sake of a test at the time. I revisited it once or twice as I made my way toward earning my undergraduate degree in college, and then was faced with it again, several times, as I earned my masters in education. It hasn’t been until recently that I’ve begun to appreciate what the taxonomy has to offer to us, though, and that’s too bad, because I think it’s a lot. Bloom’s Taxonomy has become so important to me, in fact, that I’ve spoken of it at school inservice meetings in recent years and drawn it on my classroom’s board so I can reference it during class discussions. In an era of standardized testing, ‘standards’ that are so convoluted they require special training to unpack, and the confusions brought about by artificial intelligence, Bloom’s Taxonomy isn’t only a refreshing breakdown of what we’re talking about when we say “students need critical thinking skills”; it’s also a clarifying framework that helps me explain what I do in my English class, why I don’t need to teach my students using AI, and why I should be teaching longer, more attention-demanding works, not shorter, bite-sized ones in my high school classroom.

If you’re still with me after that long paragraph, this must sound intriguing to you, too. What is Bloom’s Taxonomy, you might be asking, or, if you’re already familiar with it, Why is it worth revisiting now?

The Taxonomy: an Overview

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a pyramid-shaped representation of how we think. It’s broken into six categories. Moving from bottom to top, these are knowledge, understanding, application, analysis, evaluation, and synthesis. The lower levels are foundational. We need them to build on. You cannot apply what you do not know or understand. You cannot evaluate or synthesize knowledge unless you can understand it to begin with. The skills at the top are Higher Order Thinking Skills. We often call these Critical Thinking Skills: I’m comfortable using the terms interchangeably. Too often we say the words “Critical Thinking” without knowing what they mean. We suspect someone who is capable of “Critical Thinking” is someone who is simply very smart, but critical thinking is comprised of a discreet set of skills: analysis, evaluation, and synthesis.1 If we think about these skills discreetly, we equip ourselves to teach them more effectively.

Before going any further, we should define our terms. I’ve found that a large number of my fellow educators don’t have working definitions for two-thirds of the taxonomy. That’s too bad, because definitions help us understand, and understanding is necessary so that we can apply, and, well—clearly we’re not going to be climbing very high up this pyramid if we can’t get past its second level, are we?

Knowledge is, of course, knowing, and knowing largely means knowing facts. Facts, though they may often be denigrated as lower-level stuff—things anyone can look up—turn out to be awfully important. Facts are what we push around in our minds to make sense of things. We build them cumulatively to increase our knowledge and understandings; we compare and contrast new facts with existing ones to evaluate similarities and differences and we synthesize our understandings to form new understandings. We intuitively understand that knowledge in the form of facts is important for young children. We understand that they need to learn numbers and letters and colors and shapes—that these lumps of knowledge are foundational to the rest of their learning and understanding of our world. We seem less keen on understanding that adults need factual knowledge. What exactly do we mean by ‘republican’ or ‘democrat’ or ‘libertarian’? What are the definitions of these words we hear thrown around in our national discourse, about which we have such strong feelings but so little understanding? What do we mean when we say ‘capitalism’ or ‘socialism’ or ‘communism,’ ‘marxism,’ ‘patriarchy,’ ‘feminism,’ or ‘trickle-down economics’? These words carry both denotations and connotations, and many of us understand them more fully in the emotion-laden latter way than the matter-of-fact former. Some of these words may, in fact, have multiple or fluid definitions, or might have different meanings to different people in different contexts.

Understanding, like knowledge, perhaps suffers for being superficially understood. To be elementary about it, we can know that 2+2=4, and then, at a higher level, we can understand why these numbers combine the way they do. Our kindergarten teacher can take two pennies from one side of the table and slide them toward two pennies on the other side of the table, and when they came together we understand that 2+2=4. It is no longer a memorized fact, but a process we comprehend. When she slides two pennies away, we understand that 4-2=2, and perhaps gain an important building block that will let us apply our understandings of math to our personal and financial lives. Similarly, in a good biology class, students leave knowing that photosynthesis takes place, and in a great class, perhaps by virtue of an instructor drawing diagrams on a board or letting students look at cells under slides, students understand how this process happens.

Application is one of my favorite categories, and another I suspect is so self-explanatory that I don’t need to define it or offer up many examples. Though it’s in the lower half of the pyramid, I don’t think it’s a shabby skill to aspire to. In fact, if my students can’t apply something I’m teaching, I’m not sure I should be teaching it to begin with. Fortunately, from Beowulf to The Canterbury Tales to Othello, Pride & Prejudice, Frankenstein, Song of Solomon, to Death of a Salesman, I’ve learned to make all of the literature I teach relevant and applicable for my students. Likewise, I can offer my students ways that my instruction in grammar, punctuation, Romanticism, Modernism, Post-modernism and research-writing are relevant and applicable to their lives. If you’re teaching and your students want to know why you’re doing something, I hope your answer is never “because it’s in the curriculum,” or, worse, “because it’s a tested standard.” You should be able to explain how your material is applicable in the real world or, that failing, explain how it’s a building block for future learning that will be applicable.

Analysis is where defining the levels of the taxonomy most eye-opening for my students—and for many of my colleagues. Too often, the word ‘analyze’ in a prompt makes students think ‘Okay, I have to write-out an answer,’ or, ‘Okay, so I have to write a paper.’ But analysis is more specific than that: it’s the act of breaking something into its component parts and seeing how those parts work—or don’t work—together. In English class, we might analyze a poem to see how its component parts—word choice, figurative devices, sound devices, occupation of space on the page, etc.—work together to develop meaning (or to do whatever it is the poem does). In a medical lab, technicians might put blood into a centerfuge to spin it down, then analyze it to get red blood cell counts, white blood cell counts, check for iron levels, or look more closely at those red blood cells under a microscope to see if someone has sickle cell anemia. Student athletes today watch a lot of film: my football, basketball, and soccer players become experts in analyzing the other team’s defense to see how they work, while the baseball coaches I know show batters film to analyze their swings starting from the ground up with their batting stances.

To Evaluate is another word that far too many people take to mean ‘write a paper’ or ‘answer this question.’ To evaluate actually means judge based on criteria. Evaluating is a skill my students enjoy because they enjoy brainstorming for criteria and they love to judge. “What are the criteria for a good basketball point guard,” I might ask, or “What are the criteria for a good romantic comedy?” When we peer evaluate, we come up with rubrics together to decide how we should be judging one another and ourselves. How will we know we’re successful? How will we know what degrees of success we have achieved? Can we quantify such things? For an introductory class discussion, “What are the criteria for judging a good teacher?” is one of my favorite questions: evaluating teachers is famously difficult, and students love to do it.

Synthesis, sometimes called creation, is the top of the pyramid. Synthesis happens when we combine our existing knowledge and understandings to form new ones. Doing this requires all of the previous levels. We must know and understand a number of matters, must be capable of applying those knowledges and understandings, must be able to break them down analytically, and must be able to evaluate whether they are worthy or proper for our current synthesis (or how they might best be synthesized) and then, perhaps, evaluate how well we have done this work of synthesizing before refining our syntheses in second or third rounds of work.

Bloom’s Taxonomy as a Lens onto the Troubles with Standardized Testing

In the face of the standardized testing movement and the expectation of 100% student passage rates ushered in by No Child Left Behind legislation, schools narrowed their curricula to prepare for these ‘skills-based’ tests. Replacements for this legislation have left heavy emphasis on standardized tests and their passage in place. In English/ Language arts, this has meant that schools that are ‘failing’ or ‘on the bubble’ have lost core subject electives and seen large swaths of their ‘knowledge-level’ curricula excised in favor of ‘skills-based’ test preparation. Units that formerly provided historical contextualization, such as those discussing The Enlightenment, Romanticism, Transcendentalism, Naturalism, Modernism, and the like were put on the chopping block beside other ‘untested’ materials like cursive writing and grammar. In place of whole novels, students received excerpts. In place of written papers, students were assigned multiple-choice assessments. This ‘narrowing’ in favor of test-prep for ‘skills’ dramatically reduced the amount of knowledge, the base of the pyramid, that students had to work with. Compared to previous generations, students of the last twenty years have grown up in a relative knowledge vacuum and lack historical contexts and philosophical frameworks to think about their lives. Paradoxically, with greater access to knowledge than ever, many students today ‘own’ less knowledge than previous generations. Filling this vacuum, students have their cell phones and access to social media. Is it any wonder they’re one of the most materialistic generations in recent history? That they are one of the most anxious and depressed?

While standardized testing eroded the bottom of the Bloom’s taxonomic pyramid, it also lopped off the top. It’s easy to test understanding and applications of skills on standardized, fill-in-the-bubbles tests. It’s harder to assess abilities to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize. Critical thinking-intensive assignments such as research papers have been deemphasized and removed from curricula. In many situations where tests have gone so far as to assess higher-level skills, the portions of the tests devoted to them are so small that students can ‘pass’ the test while failing the portions related to higher order thinking skills. School curriculum specialists and test-prep czars know this and encourage their teachers to go after the low-hanging fruit to improve all-school and all-district passage rates. This improves school district ‘metrics’ to the benefit of administrators touting their numbers and to the detriment of students who leave schools without real knowledge or skills.

Disappointments in HOTS Land

There’s a perennial concern that our students are lagging in their development of Critical Thinking and Higher Order Thinking Skills. In the face of this concern, there’s an argument that these skills need to be explicitly taught more often and that our students need more experience with HOTS-intensive assignments such as “Project-Based Learning” and “Real World Learning” projects. While I’m inclined to agree that analysis, evaluation, and synthesis need to be modeled and practiced more often—and that “project-based" and “real world” learning are worthy additions to curricula—my opinion of the HOTS deficit runs contrary to the ‘we don’t practice enough’ argument. I believe we have deficits in these ‘top’ areas because we have deficits in foundational knowledge, understanding, and application at the bottom of the pyramid. I think too many students are going through school rotely filling out worksheet assignments without gaining real knowledge or practicing real skills. Having been numbed by assignments whose application and validity students can’t recognize for the sake of multiple-choice tests that don’t matter to them, students have lost faith in the notion that their educations are valuable to them. Many have stopped investing in them.

From this perspective, it’s not our deficits in HOTS that we need to worry about, but our deficits in knowledge, understanding, application, authenticity, and legitimacy.

What AI Has Brought Into Focus

I’m not an AI enthusiast, but I’m not one of those who’s so delusional as to think we can put the genie back into the bottle, either. Certainly it is, as they say, ‘a powerful tool.’ That said, given the chance, most students will take advantage of AI to ‘outsource’ as much work as they possibly can just as, to maximize profits, employers around the world are going to be ‘outsourcing’ jobs to computers. There will likely be divides between ‘AI-haves’ who can use the technology well and ‘have nots’ who cannot. The existing economic ‘haves’ will likely benefit disproportionately over the ‘have-nots.’

While the ability to make effective use of AI is no doubt already an important skill, I don’t know that K-12 instructors need to ‘teach’ students to use AI so much as we need to model how to use it correctly and appropriately. And frankly, it seems to me that using AI well is largely a matter of having access to a wide base of knowledge and understanding and complimenting these intellectual assets with strong critical thinking skills. In short, the people who are going to be the best at using AI will likely be those who need it the least, and in a world evolving toward a heavy reliance on artificial intelligence, I still need to equip my students with real human intelligence in my classroom.

What Teachers Should Do Now

In the modern era, I think the best educations we can offer students today and tomorrow will look a great deal like the educations we offered them in the recent past. Students should read more often, read more broadly, read more sustainedly, and read more deeply. We as teachers should eschew shallow ‘test prep’ learning and the lure of shiny AI-instruction tools. The students best equipped to live in a shallow, attention-stealing, tech-driven world will be those who have broad knowledge bases, the patience of real learners, and deep knowledge and understandings across a range of domains. We should work slowly and meaningfully to create students who can read not only traditional ‘English class’ texts, but also the texts of other classes and the ‘texts’ of math problems, scientific questions, charts, graphs, and figures. I think we should do as much of this preparation as possible in environments that are lower pressure than the standardized testing environment we have recently created and more screen-free than many pushing AI-integration seem to want for us. If we do so, I think we can produce deep, happy, intelligent, and productive young adults. If not, I suspect we’ll have shallow, impatient, anxious, unskilled, and unsuccessful ones.

If you enjoyed this essay, you may also like my popular essay Teaching Isn’t a Science—or an Art, my post Four Graphic Representations for High School English Teachers, my poem Forests, Trees, or my short story Cheaters. A great deal of my educational thought is distilled in dramatic fashion in my popular novel Why Teach?, which boasts high ratings on Amazon and Goodreads. The first chapter is available for preview here, and buying a copy is a great way to support my newsletter!

Peter Shull is a Midwestern novelist, essayist, short story writer, and educator. To support him, buy his novel Why Teach? about a young high school teacher navigating the treacherous waters of small town life and the damning consequences of high-stakes testing. It’s available at Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo.

I’ve learned to be a little dubious of myself when I assert claims like “critical thinking is comprised of a discrete set of skills,” and so I’ve done some poking around to double-check my claim. Unsurprisingly, there are a number of definitions and frameworks for “critical thinking.” Some of them also include ‘information gathering’ and ‘self-reflection and self-analysis’; some are built for particular tasks, ie: “critical thinking for problem solving.” Surely different disciplines and domains have their own definitions and frameworks. Through the lens of Bloom’s Taxonomy, some of the sources I found seem to suggest that “application” is also a critical thinking skill, while most lean heaviest on “analysis” and “evaluation.” For a few minutes, I wondered if these two “critical” (“breaking down” and “criticizing”) skills might be separate from synthesis (“creation”), which is really a kind of building, or assembly. Perhaps, I thought, synthesis deserves its own category. “Synthetic thinking” didn’t sound so hot, though, and “creative thinking” sounded almost elementary, so I’ve ultimately decided to leave it alone and continue to think of “synthesis” as a type of “critical” thinking. I seem to be consistent with the taxonomy in doing so.

If I’ve erred in my definitions of terms—if ‘critical thinking’ and ‘HOTS’ shouldn’t be equated, or if you have another clarification or suggestion for me—I’d appreciate hearing about it in the comments!

Great post. Your students are fortunate to have a teacher who thinks in these terms, esp as it relates to learning and preparing oneself to use AI. If students lean too much into the “A”, the output won’t be “I” enough to matter.

I’d written about this in a note and didn’t want to be overly negative about the flip side of what I saw in some really sharp, well-spoken kids that day. What struck me as interesting (and also kind of sad) was the students who struggled to speak about their projects didn’t hesitate or verbally fumble to find the right words. They just yammered away in borderline nonsensical ways, sounding more like AI outputs than 18 year olds, with filler words and SAT words sometimes used incorrectly. I thought of this as I was reading about Bloom’s pyramid. Try to apply before you understand or have the right knowledge and the whole thing falls apart, real quick-like.

This is such a remarkable labour of love. I can't imagine the sincerity and effort you must have put into writing and formulating this one. Thank you!