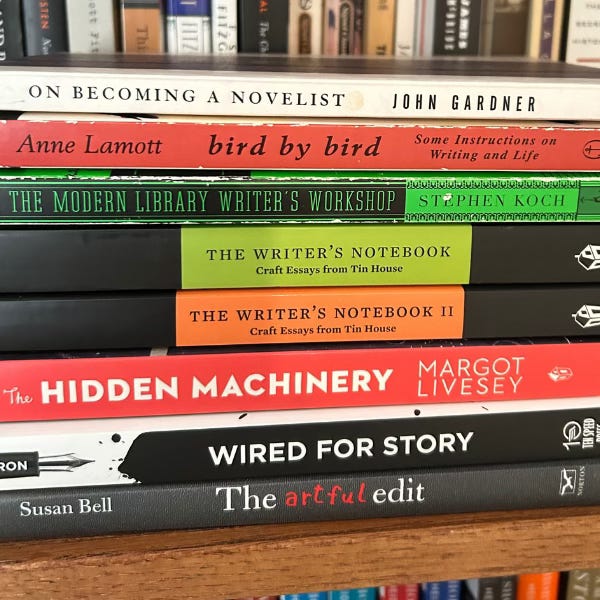

I see a great number of strong fiction writers on Substack, but also recognize there are many on the platform who are newer to the fiction writing game. Many are trying to get sophisticated educations on the art of writing by reading about craft and process here, online. As a writer who’s been there, I can’t help but think Better here than YouTube or Tiktok. As a teacher, I can’t help but feel it would be nice to offer up some more formal direction. Here’s a quick ‘curriculum’ of seven-ish books I would suggest to an aspiring author of higher-quality or ‘literary’ fiction today. Picking up anything from it could help an aspiring writer two-fold: 1) you could get invaluable writing advice, and 2) in reading a physical book, you could spend several hours offline and away from this online cesspool of attention theft. Three of the books below are comprehensive ‘catch-alls’; two comprise a favorite two-volume collection of essays by assorted authors; one is a favorite single-author collection; one is my favorite book on story and structure; and the last is my preferred book on self-editing. Several of the books are bunked with secondary-level choices: there’s plenty of flexibility if your local library doesn’t have some of the books I recommend. If I was only going to recommend one comprehensive book from the whole set, I think it might be the third on my list, but I think highly of every book I’ve mentioned. Without further ado:

1) On Becoming a Novelist, John Gardner

John Gardner has rigorous, exacting expectations for the novel. He expects character development; not plot, but story; and prose and dialogue that don’t merely showcase the writer’s ear for conversation but serve the character development and story. In an age of Nanowrimo, Save the Cat, ‘content creation,’ and schemes to write 20 novels as quickly as possible, there’s something refreshing in Gardner’s high standards. Gardner expects novels to be art. He expects novelists to be artists. He’s aphoristic and infinitely wise. My copy of On Becoming a Novelist, like my copy of his The Art of Fiction, is heavily underlined and annotated. It seems to me that The Art of Fiction is more popularly mentioned (perhaps it’s better for short story writers?), but if I could only have one of his books, it would be On Becoming.

There is, I think, a danger in reading Gardner, and I’ll be forthwith about it: Gardner’s expectations can be so high as to be paralyzing. Who can write that well? If perfection is the standard, why should we bother? In truth, when I’m reading Gardner, I feel I can’t write—and when I read novels by Gardner, I’m not sure he always (ever?) lives up to his own standards. Gardner’s books are texts on writing that I prefer to ingest, process, and then look back on a few months or years after reading them; immediately afterward, though, I suffer a kind of writerly indigestion or hangover: for a few days or a week, I can’t write at all. I’ve listed Gardner first because I think he’s the best; that said, I don’t think he’s for everyone, and I don’t think he’s the best place to start. For the best place to start, I would make use of one of the next two books.

2) Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott

Lamott’s Bird by Bird is, in many ways, the antithesis and antidote for Gardner’s exacting books on writing. Lamott encourages us to write sentence-by-sentence, visualizing postcard-sized portions of the text every day, and wants us to trust in the process by daring to write ‘shitty first drafts.’ If Gardner sometimes feels like he’s saying “You can’t” because his expectations are so high, Lamott is saying, emphatically, “You can, and you ought to get started right now.” I regularly reread Lamott every five or six years, often six or twelve months after my most recent completion of one of Gardner’s books. When I put her book down, I’m always ready to pick up my pen.

3) The Modern Library’s Writer’s Workshop, Stephen Koch

If I was only going to recommend one book on this list—a desert island book, say, or the single book you might take on a ‘writers vacation’—it would be Koch’s text. Koch’s book strikes me as the happy halfway point between Gardner’s and Lamott’s. He headed the creative writing program at Columbia for two decades, and his book synthesizes his readings of a number of great authors’ books on writing with his own experience working with two decades’ worth of students. It includes many quotable nuggets of wisdom, addresses all phases of writing and ‘the writer’s life,’ and makes use of an accessible, encouraging tone.

4) Tin House Writer’s Notebook Volumes I and II, Various Authors

There are a great number of great essay collections on writing that I could put in this spot or the one below where I’ve placed Margot Livesey: I think that the collection Bringing the Devil to his Knees by Baxter and Turchi is very good, for instance, and I’m fond of Frank O’Connor’s The Lonely Voice. Francine Prose has a good book called Reading Like a Writer. If you specialize in short stories, I think that Writing in General and the Short Story in Particular by Rust Hill is very good. On that note, Douglas Bauer’s The Stuff of Fiction: Advice on Craft is excellent and perhaps ought to be on my ‘master’ list on the strength of two or three of its chapters alone. Daniel Alarcon’s book The Secret Miracle poses a list of popular questions to a number of successful and popular contemporary authors (~fifteen years ago) and compiles their answers—and I haven’t even gotten to The Paris Review Interviews Volumes I-IV, the New York Times Writers on Writing Volume I & II, or anything put out by The Believer magazine such as their The World Within or The Believer Book of Writers Talking to Writers. (Reading any two or three books I’ve listed above would shed tremendous amounts of light on writing for the newcomer.) The Tin House Writer’s Notebook volumes are the ones I recommend here because they’re accessible, nicely formatted, include some great examples within the essays, and each has a handful of real gems. If forced to point a new writer toward three or four (or five) of the others above, I would point to the Bauer text first, then the Baxter and Turchi, then Daniel Alarcon’s, then the Paris Review collections, and finally Francine Prose’s book after that.

5) The Hidden Machinery, Margot Livesey

Livesey’s The Hidden Machinery is a delight. In it, you can partially trace the author’s own development as a writer as she examines the works and techniques of some of her favorites including Henry James, E.M. Forster, Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Gustave Flaubert, and Shakespeare. On the Gardner-Lamott spectrum (which is apparently a thing, now, because I say it is), reading Livesey feels like getting advice as specific and mind-expanding as Gardner’s from someone who is as kind, encouraging, and supportive as Lamott.

6) Wired for Story, Lisa Cron

One of the last things I feel like I really 'learned’ is how to write story, and I think that makes sense because story is deceptively tricky. If feels easy—“anyone can tell a story!”—but you sit down to do it and it’s just not there. I am, I think, a ‘prose’ guy. I’m looking for a good voice. If I’m reading a book—spending time with another consciousness for several hours—I want that consciousness to be, if not an intelligent and savvy one, then at least an unintelligent and unsavvy one rendered that way by someone who is clearly intelligent and savvy.

Today, reading lit mags, highly publicized novels, and fiction on Substack, I see good and great prose written by intelligent people in many places. I see interesting reliable and unreliable voices in many places… but good prose and an interesting voice aren’t enough, and when it comes down to it, I’ve become distrustful of 'prose-y’ and ‘voice-driven’ fiction. Too often it seems like a parlor trick. T.S. Eliot famously said that ‘plot is the bone you throw the reader while you go in and rob the house,’ and it seems to me in recent years that an ‘interesting/over-the-top voice’ or ‘poetic prose’ are the bones many authors throw publishers and the public when they don’t actually have stories to tell. When an author has both a strong written voice and a story to tell, I think it’s magic, but I feel I see this less and less. When it comes down to it, given the choice, I’d prefer a simpler and more straightforward voice that came with a story than a book that was the other way around.

Which is all to say: Cron’s is my favorite book on story, why story matters, how it works, and how we can do it. She has a second book, Story Genius, which I enjoyed and which definitely has some nuggets of wisdom (and apparently a third, Story or Die, which I haven’t read), but I prefer this first text. Other texts on story worth reading include, yes, Save the Cat (it’s perhaps overly prescriptive, but perhaps not as overly-prescriptive as many people suggest, and it gives newcomers something to start from), and Stuart Horwitz’s Book Architecture, each of which I have found helpful.

7) The Artful Edit, Susan Bell

I think the ‘go-to’ text in the revisions category might be Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Browne and King—and I do think this is a very good book—but if I only had one book on self-editing, it would be Bell’s. The Artful Edit includes some of the ‘nuts and bolts’ stuff of micro- and macro-editing, but feels more generous in its sharing of a wise and philosophical approach to reconsidering one’s own work than any other texts I’ve read. It also has an outstanding section on Fitzgerald’s editing of The Great Gatsby with the help of Maxwell Perkins (this chapter also appears as an essay in one of the above-mentioned Tin House essay collections) and a number of vignettes on how other authors and artists in other disciplines approach their revisions.

In Closing: a Warning

For all of the value of craft books, there’s only so much studying of craft that one can do. Reading craft books can become a trap in a number of ways: it can swallow up all of your writing time; it can make you feel like you’re making progress as a writer when you’re actually not putting any words on the page; and it can become too prescriptive-feeling, preventing you from doing any writing since you don’t feel like you can write to the standard or in the style the books suggest. Reading books on craft can also take the place of reading model fictions, and I’ve come to believe largely in model fictions: those works that resonate with your own internal iron string; those that are most closely adjacent to the works you want to write. I think every working author ought to have a small stable of inspirational authors who they can go back to over and over, reminding them of what they love and what kinds of writing they want to do. When I begin reading too many ‘how to write’ essays, I begin to feel a sort of malaise; when I open an actual book, I think: That’s right, it’s just a sentence after a sentence after a sentence—and then I can start writing again, a sentence after a sentence after a sentence, and the writing, ultimately, not for days or weeks or months, but years, is what gets you there.

Enjoy the process,

Peter

Peter Shull is a Midwestern novelist, essayist, short story writer, and educator. To support him, consider buying his novel Why Teach? about a young high school teacher navigating the treacherous waters of early teaching and the damning consequences of high-stakes testing. It’s available at Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo.

Stephen King, On Writing, and Chuck Palahnuik, Consider This, are both excellent. Practical, a pleasure to read, and contemporary.

My favorite craft piece of writing is Ann Patchett's THE GETAWAY CAR, an essay (a very, very long essay) in her book THIS IS A STORY OF A HAPPY MARRIAGE.