Hi Friends,

It’s back-to-school season, so I’m shifting my focus temporarily for the benefit of my fellow teachers. I don’t think I’m sharing earth-shattering news if I say education is in crisis right now. Teacher turnover is high, the number of young people entering the profession is low, the number of ‘nontraditional teachers’ (of which I was once one) is increasing, rising costs of public education and college are making people question whether education is worth the expense, AI has thrown wrenches into the works, and our rapidly changing economy has made it difficult for educators to determine how best to prepare our students. For my part, I believe in education. I believe that reading and writing are integral to thinking, and that if we want to have a successful society, we need a society of capable readers and writers. (I know, I know…) I also believe that if we writers want anyone to read our beautiful fictions and sophisticated essays in coming decades, k-12 teachers are going to need to equip them with the skills to do so now.

This said, I know that most of my audience is here for my fiction and thoughts on writing, so I still plan to mix in posts to this end. I’ll have 10 of my favorite essays on writing fiction next week, a post addressing Bloom’s Taxonomy the week after that, and then, at probably a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio, posts on education and fiction writing for the next few months. If you’d like to skip some of my posts or check out, no hard feelings. I’ll hope to see you around again in the fiction world at a later date. Anywho, today’s post:

1) The Gradual Release of Responsibility Model

The first of the graphic representations I think about most often as a high school English teacher is The Gradual Release of Responsibility model. This model suggests that teachers should take ‘high’ ownership of material early to present and model concepts and behaviors, then work alongside students while they work, and then step back to watch from a distance while students perform on their own. As a small hiccup with regard to this one, I do think there is value in an ‘anticipatory set’ to ‘key’ the students for their learning: that is, the teacher presents the task or challenge to students before modeling how it is done so that they begin engaging independently before the teacher swoops in to ‘feed’ them the skills or knowledge.

As an example, I might show my students a poem at the beginning of the year and ask “What does it mean to analyze? How would you go about analyzing this poem and writing an analytical essay on it?” When I set them to this task on their own before teaching them how I would do it, my subsequent instruction becomes more meaningful because I’m working with them on something they have already engaged with independently.

The Gradual Release of Responsibility model works in ‘macro’ situations such as thinking about the entire school year (I take high ownership early, and really maintain pretty high ownership in a number of ways until February, and then begin releasing a great deal in March, April, and May) and in more ‘micro’ situations such as the planning of a two or three week unit or even a single class period. In fact, a typical class period for me includes my highest ownership in the first 10-30 minutes, and in the last 10-30 minutes of my 85 minute periods, my students typically ‘own’ that time to work independently or in groups.

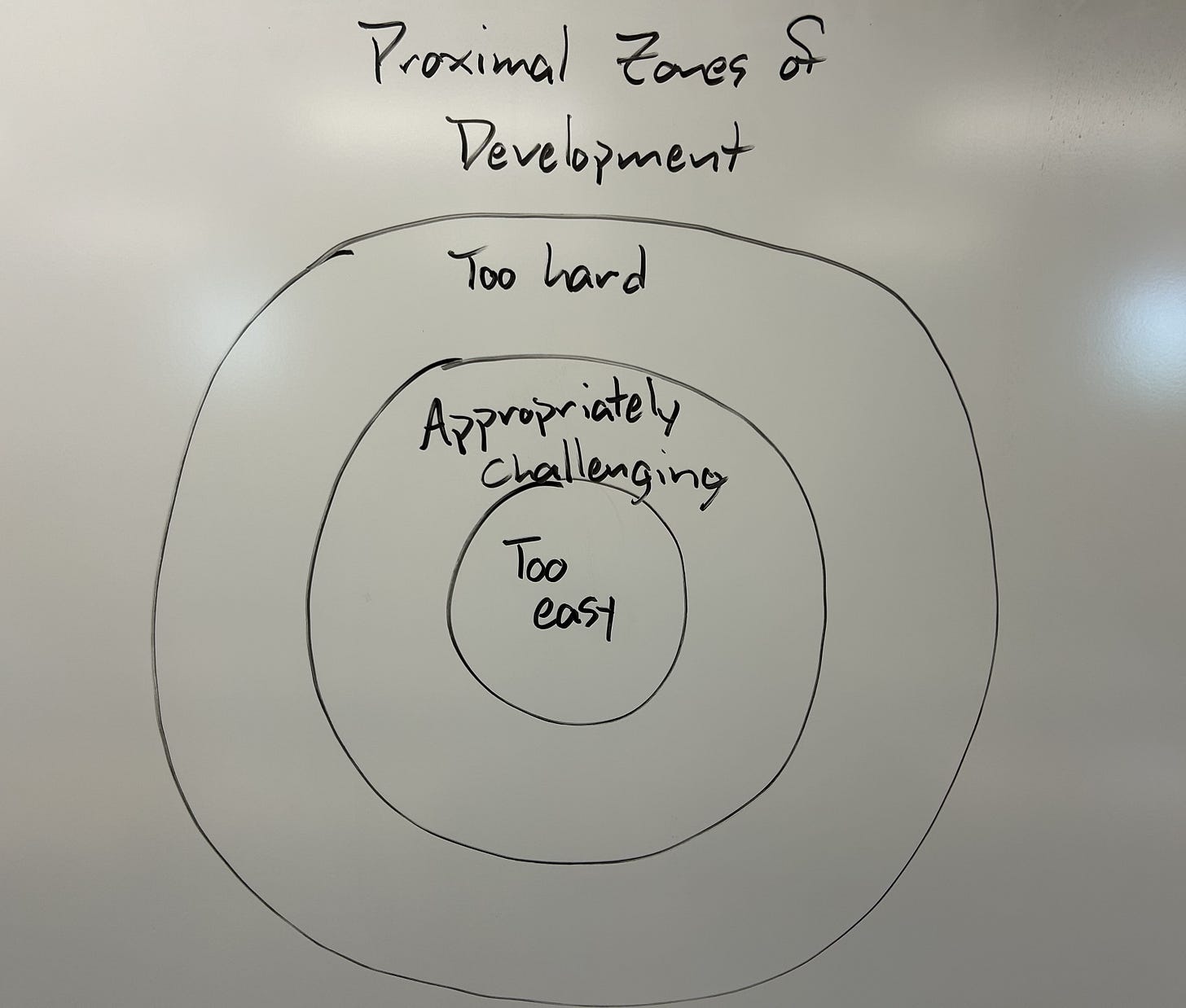

2) The Proximal Zones of Development

The idea embodied by the Proximal Zones of Development model is that some material is too easy for students to learn from and other material is too hard. Teachers are advised to stay in the ‘Goldilocks’ zone of material that is ‘just right.’ I like to take this concept a little further and argue that there is a ‘range’ within the ‘just right’ section, and that early in the year (or in a unit), teachers should hew close to ‘too easy’ portion of the circle and later in the unit they should creep toward ‘too hard.’ As an example: the bread and butter of my senior Literature class is determining meaning and arguing for how that meaning is developed. I teach this skill all year long. Early in the year I start with children’s stories, allegories, parables, and zen koans. We work with relatively easy poems and short stories before moving to relatively straightforward novels and plays. As the year progresses, we work with more challenging material: Frankenstein, or The Crucible. In January and February we typically consider ‘challenging’ works such as Othello, Hamlet, and Song of Solomon. At the end of the year, I will confront my students with material—typically dense poems, short stories, and excerpts from longer works—that are so intricate and/or ambiguous that I feel I would have trouble answering the questions “What does this mean?” and “How is this meaning developed?” In anticipation of the challenges of the rest of our students’ lives, I think we must move to the ‘too hard’ portion of the proximal zones and ask “What should we do when we don’t know what to do?” Confronting students with great challenges and teaching them to keep their chins up and ‘grapple’ or ‘muddle through’ after we have built skills with easier material ultimately, I think, helps them build confidence and self-efficacy.

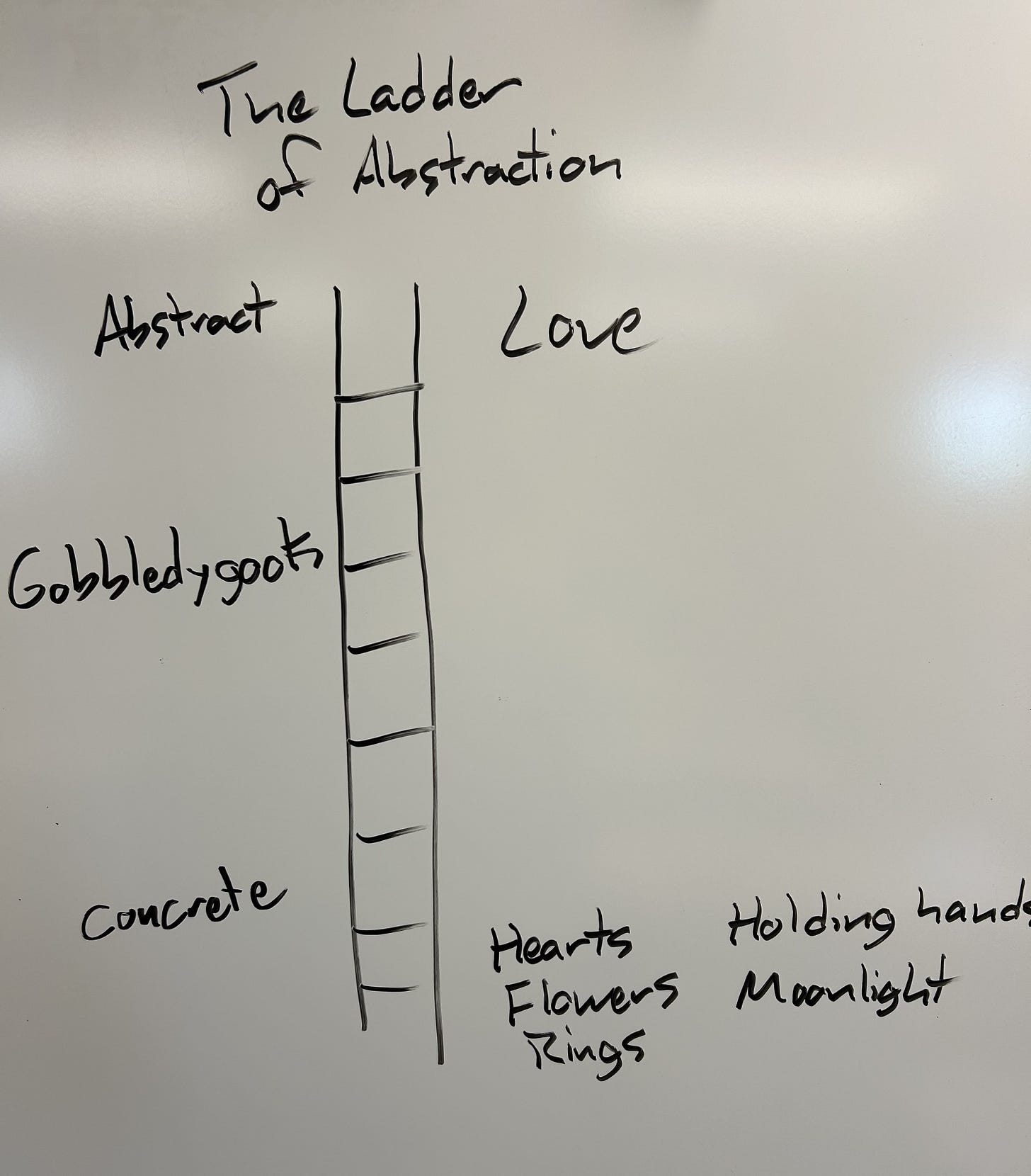

3) The Ladder of Abstraction

S.I. Hayakawa’s Ladder of Abstraction is a model that helps writers think about making their writing more specific and concrete—and therefore more comprehensible and ‘sticky.’ At the top of the ladder, we have words that are abstract: think love, freedom, democracy, struggle, or independence. At the bottom, we place the ‘concrete’ (that is, tangible) nouns that we associate with the words at the top. For love, perhaps roses, chocolate, candles, a home made meal, or held hands. For freedom, perhaps an eagle or a car. In the middle of the ladder, we have jargon and gobbledygook: words and phrases that sound good but don’t really mean anything: the legalese and bureaucratic mumblings our world has been overtaken by such as “adhering to our shared institutional values to ensure customer satisfactions and positive consumer outcomes.” Throughout the course of the year, I am forever telling my students they need to "be more specific” and “offer more examples”; the ladder of abstraction is one of the tools that helps me broach the importance of these concepts early in the course.

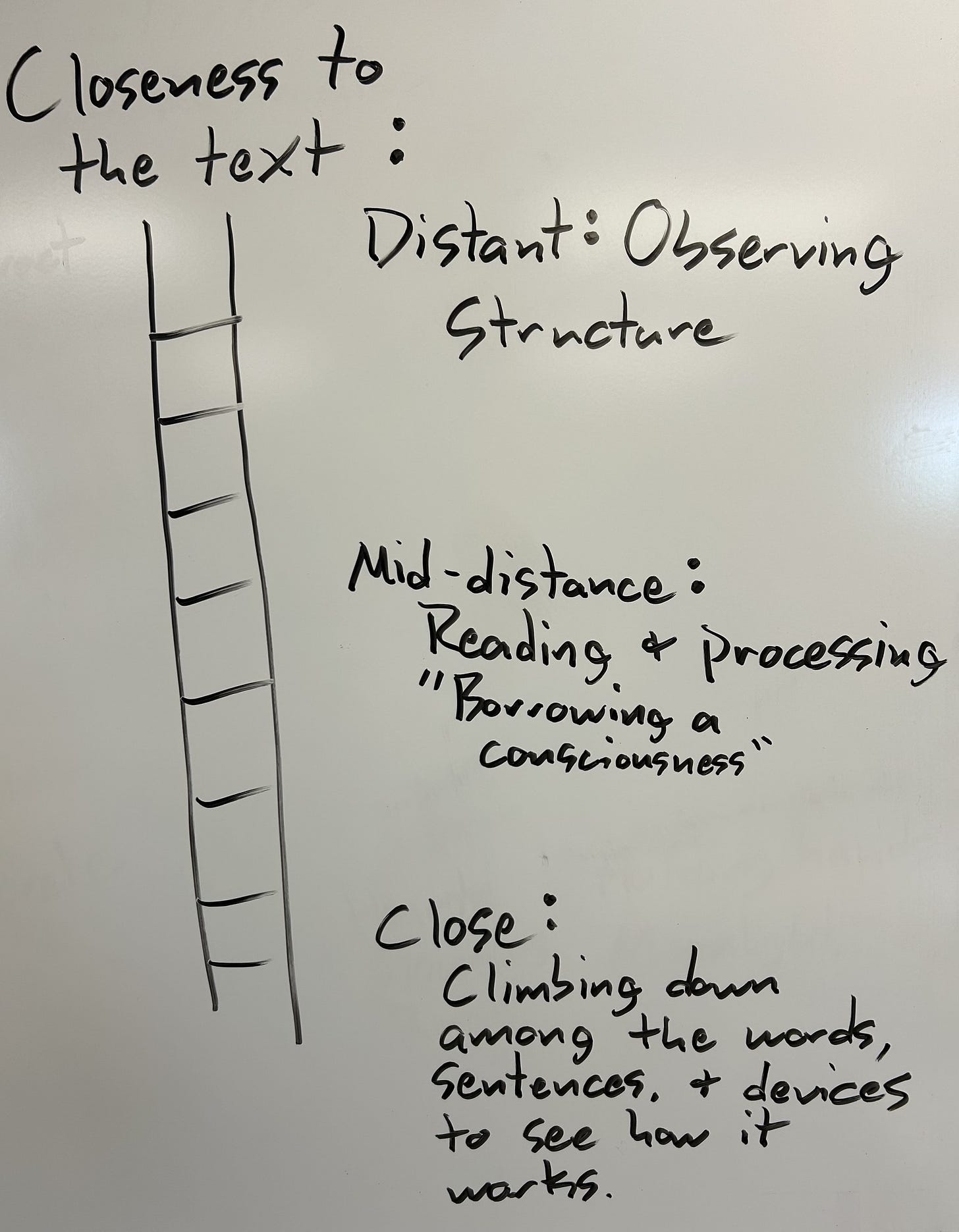

4) The Ladder of Closeness to the Text

The Ladder of Closeness to the Text is a (not exactly super-original) tool of my own improvisation. Borrowing from Hayakawa’s image of a ladder I’ve already drawn on the board, I suggest to my students that when they read they are reading a work they are typically in the middle of the ladder, at ‘cruising height,’ experiencing the ‘fictional dream’ of a work. Sometimes I refer to this as ‘borrowing a consciousness’ since we have that sensation of hearing another person’s voice in our head and ‘seeing’ the world through their eyes. When we climb the ladder of closeness to the text, we get further from the ‘dream’ and look down at it from a birds-eye position, gaining an understanding of its structure: what it’s large ‘chunks’ or ‘component parts’ are and how they work in relation to one another. (I’ll likely use words like ‘juxtaposition’ or ‘character foils’ in discussions here.) When we climb down, we move among the words, punctuation, figurative devices, and other authorial techniques to do ‘close reading’ and see how the author has done their finest detail work to impact and guide the reader.

Do you have graphic representations and models that you use while thinking about your class? Do you have questions about mine? Feel free to hit me in the comments.

As always, if you want to support me, please feel free to hit ‘like,’ ‘subscribe,’ or ‘restack.’ I’m deeply appreciative of all of the people who have bought my book, left 5-star reviews, and recommended it to others.

See you next week with some recommended essays; happy reading, writing, and teaching until then,

Peter

Peter Shull is a Midwestern novelist, essayist, short story writer, and educator. To support him, consider buying his novel Why Teach? about a young high school teacher navigating the treacherous waters of early teaching and the damning consequences of high-stakes testing. It’s available at Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Kindle Store, and Kobo.

Slightly unrelated— but do you have a general model for how you sequence each lesson/session (other than the bell-ringer — lesson — exit ticket model)? I could benefit from having something more predictable/structured for my students

What made you a nontraditional teacher in the past? Does that mean not having a degree in education?